Black Saints and the Priesthood (Brigham Young/Early Utah era)

The history of the Church regarding race and the Priesthood is interesting and complex, but can be uncomfortable to study. Read on to learn about the origins of the priesthood and temple ban, early Black members such as Elijah Able and Jane Manning James, and more.

Or, you can skip the Q&A and jump straight to "Our Take."

Timeline (1845–1903)

April 1, 1845

April 27, 1845

December 24, 1845

March 1847

April 1847

May 1847

December 1847

February 1849

February 1852

October 1861

May 1, 1873

September 3, 1875

With Brigham Young's approval, eight Black Saints serve as proxies for baptisms and confirmations in the Salt Lake Endowment house.[20]

circa June 1879

December 27, 1884

Recalling an invitation from Joseph and Emma, Jane Manning James writes John Taylor and asks to be "adopted to them as a Child."[22]

June 16, 1888

February 7, 1890

May 18, 1894

Jane Manning James is "attached" as a "Servitor" to the Prophet Joseph Smith in the Salt Lake Temple.[27]

October 16, 1894

August 31, 1903

Jane Manning James makes a final unsuccessful request for temple blessings.[30]

How soon after the death of Joseph Smith did public discussion of the priesthood and temple ban begin to come up?

Within a year of Joseph Smith's[BIO] death in 1844,[31] Apostle John Taylor[BIO] wrote of how Ham[BIO] "dishonored the holy priesthood" and of the curse that followed his descendants.[32] In 1847, Parley P. Pratt[BIO] referred to William McCary,[BIO] a Black Saint, as someone who had the "blood of Ham in him" and was "cursed as regards to the Priesthood."[33]

But wasn't William McCary ordained?

No, probably not. The only known source that may be referencing McCary is from the Voree Herald which claimed that Orson Hyde baptized an "Indian" whom he "ordained to go out among the churches and call himself a Lamanite prophet."[34]

McCary met with Brigham Young and other Church leaders in 1847 to discuss a variety of topics including racism and priesthood and there is no indication that McCary was a priesthood holder in the meeting minutes.[35]

When did Brigham Young begin to teach about the priesthood and temple ban on Black Latter-day Saints?

In 1852, Brigham Young[BIO] publicly announced that Black Saints could not hold the priesthood.[36] However, he privately discussed with Church leaders issues relating to interracial marriage in 1847[37] and the priesthood restriction in 1849.[38]

Was Brigham Young okay with Black Latter-day Saints having the priesthood before that?

Possibly. In March 1847, he referred to Quaku Walker Lewis,[BIO] a Black priesthood holder, as “one of the best Elders."[39]

What were the stated reasons for the restrictions?

In 1847, Elder Parley P. Pratt[BIO] referenced the curse of Ham as the reason for priesthood restriction.[40] In February 1849, Brigham Young specifically mentioned a priesthood restriction as a consequence of the "curse of Cain."[41]

Could any of these reasons be traced back to Joseph Smith?

Possibly, but there are no records contemporary with Joseph that indicate he taught or established a policy that Black Saints were to be restricted from the priesthood or temple ordinances.

However, Joseph Smith viewed Black people as descendants of Cain[42] and subject to the curse of Canaan.[43] Joseph Smith's translation of the Book of Abraham described a lineage-based priesthood ban.[44] Decades later, some Church leaders also recalled him teaching privately about a priesthood restriction for Black people.[45]

Related Question

Did Joseph Smith implement a policy to restrict Black members of the Church from the priesthood and temple ordinances?

Read more in Black Saints and the Priesthood (Joseph Smith era)

Was the restriction based on a revelation?

Possibly. In February 1852, Brigham Young said, “If there never was a prophet, or apostle of Jesus Christ spoke it before, I tell you . . . they [Black people] cannot bear rule in the priesthood.”[46] However, modern scholars have debated whether the restriction was based on revelation or not.[47]

In the 1978 Official Declaration, it states that "Church records offer no clear insights into the origins" of the ban, but affirmed the belief of Church leaders that "a revelation from God was needed to alter this practice."[48]

Did Brigham expect the ban to be lifted someday?

Yes. Brigham felt he was powerless to lift priesthood restrictions of his own accord.[49] He instead taught that the "time will come when [Black Saints] will have the privilege of all we have the privilege of, and more."[50]

Lorenzo Snow also thought the ban might be lifted at some future point.[51]

Did anyone teach that the priesthood restriction was related to the pre-mortal existence?

Yes. In 1853, Orson Pratt[BIO] wrote an essay that suggested that Black people "were cursed, pertaining to the priesthood" and were less faithful in the pre-mortal existence.[52] Emily Spencer[BIO] also wrote a poem in 1880 that referenced this concept.[53]

Did racism play a major role in the implementation of the priesthood ban?

Possibly. Church leaders used racist rhetoric when explaining the priesthood and temple restrictions,[54] and the restriction itself reflected racist policies and attitudes common to nineteenth-century America.[55]

Were there any other factors that could have contributed to the priesthood ban?

Possibly. Brigham Young, along with many white American nineteenth-century scientists,[56] believed that interracial marriage would produce widespread infertility.[57]One went so far as to say that interracial marriage could result eventually in the extinction of the human race.[58]

Brigham also believed that interracial marriages would make their descendants ineligible for priesthood and temple blessings.[59]

Did any other churches in America have a similar policy?

Yes. Many white American Protestant congregations segregated out Black membership, prompting Black members to form independent congregations.[60] White Protestant churches frequently banned Black people from positions of leadership.[61] However, several white-dominant churches (e.g., Catholics, Presbyterians, RLDS) did ordain Black members.[62]

Was this policy motivated by a desire to be more like mainstream Protestant churches?

No, probably not. The Church publicly embraced polygamy at this time, which was hugely unpopular[63] and the Saints were also leaving the United States.[64] It seems unlikely that the Church would have implemented the priesthood and temple ban to gain acceptance with mainstream Christianity.

How did Black members of the Church feel about this policy?

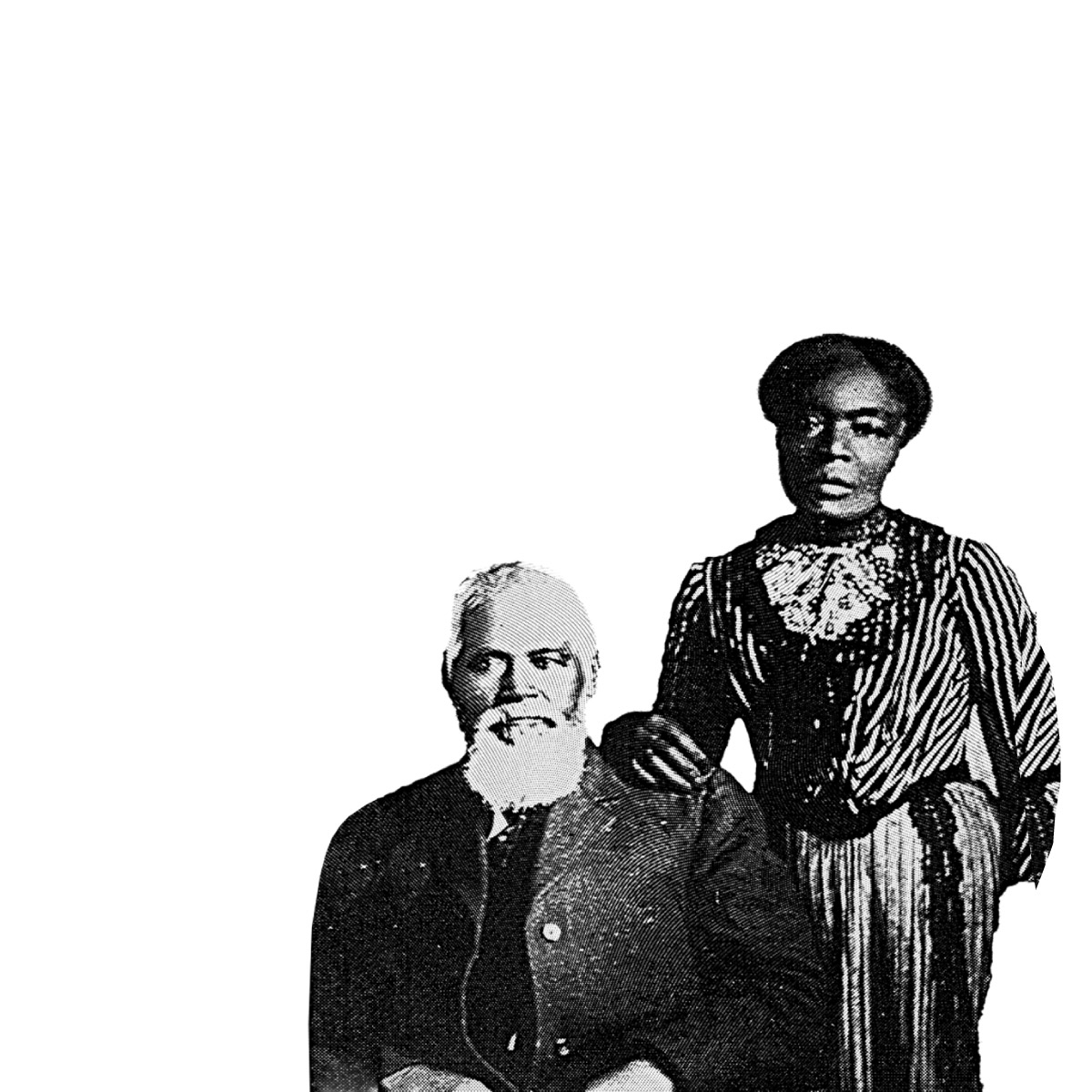

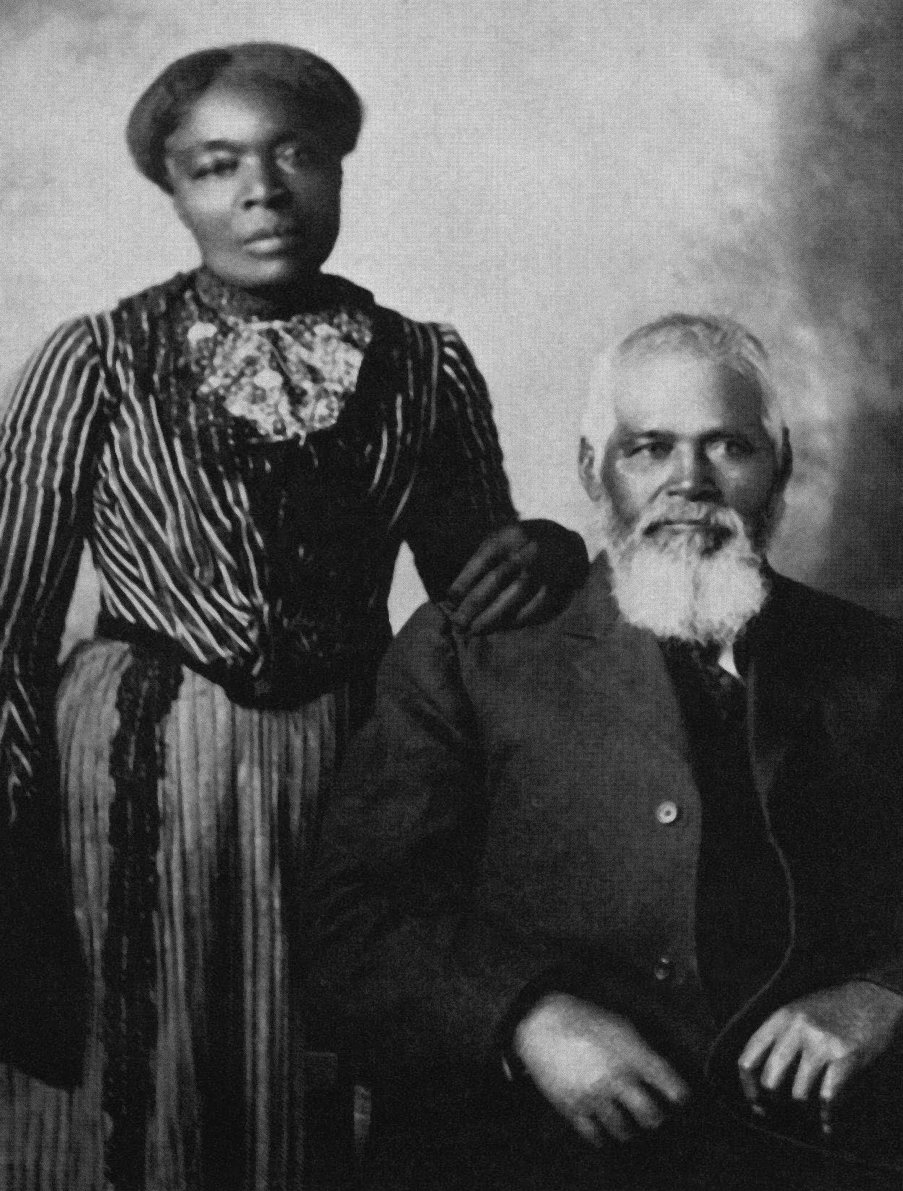

Some Black members accepted it and stayed faithful,[65] and others left the faith.[66] The petitions of Elijah Able and Jane Manning to receive temple ordinances were repeatedly denied.[67] However, they remained faithful until the end of their lives.[68]

Did anyone oppose or question this policy?

Occasionally. In 1849, Lorenzo Snow[BIO] asked when the policy would be lifted.[69] There are also some council meeting minutes towards the end of the nineteenth century where questions about these restrictions were brought up for discussion.[70]

Elijah Able and Jane Manning James, among others, challenged their exclusion from priesthood blessings.[71]

Were any members disciplined for opposing the priesthood restriction policy?

No, probably not. There are no known records of discipline for opposing the priesthood restriction. However, Church disciplinary records are generally closed, so research on disciplinary actions is limited.[72]

Were any members disciplined for interracial marriage?

Yes. There were at least two instances of discipline for interracial marriage. In 1856 Centerville, Delaware, William Knopp[BIO] married a plural wife of African ancestry.[73] His branch president excommunicated him for "contempt of council" and “mingling with the Seed of Cain.”[74] Then in 1889, Hyrum B. Barton[BIO] was excommunicated for his marriage to Laura Jane Berry.[75]

How did they determine who was Black to enforce the ban?

Physical appearance,[76] admissions,[77] and possibly "impressions."[78]

Did any African-descended members that "passed for white" receive priesthood or temple ordinances?

Yes. Some individuals with African ancestry who "passed for white" were endowed and sealed (see below). There is no known record of any of the children of these couples experiencing priesthood or temple restrictions.

Date of Endowment | Where | Endowed and Sealed African-Descended Saints |

December 24, 1845 | Nauvoo | Sarah Ann Mode Hofheintz,[BIO] wife of Peter Hofheintz[BIO][79] |

April 20, 1861 | Salt Lake Endowment House | Johanna Dorothea Louisa Langeveld Provis,[BIO] wife of Richard Samuel Provis[BIO][80] |

June 13, 1863 | Salt Lake Endowment House | Rebecca Henrietta Foscue Bentley Meads,[BIO] wife of Nathan Meads[BIO][81] |

April 8, 1903 | Salt Lake Temple | Harriet Elnora Burchard Church,[BIO] wife of Thomas Holiday Church[82] |

Are there any Black members that "passed for white" that were denied priesthood or temple ordinances?

Yes. In 1885, an unsuccessful request for sealing to a white man was made on behalf of Laura Jane Berry,[BIO] an African-descended member who “passed for white."[83]

In addition, although he did not "pass for white," Nelson Ritchie[BIO] claimed Cherokee heritage.[84] His bishop, John Whitaker, denied Ritchie temple ordinances as he "felt that he had negro blood in him."[85] However, Ritchie was posthumously endowed and sealed a decade after his death—which was not generally allowed.[86]

Did Joseph Smith or Brigham Young revoke Elijah Able's priesthood ordination?

No, probably not. Some late second and thirdhand recollections claimed that Joseph Smith revoked his priesthood, but the historical evidence seems to contradict this report.[87]

Were there any other deliberate exceptions in the early Utah era where men known to have Black ancestry were ordained to the priesthood?

Yes. Moroni Able,[BIO] a son of Elijah Able, was reported to have been ordained to the priesthood on his deathbed.[88] Deathbed priesthood ordination, later discouraged, was a known practice at the time.[89]

Were there ever any exceptions made for Black members worshiping in the temple?

Yes. On at least one occasion, Brigham Young authorized a group of Black Saints to perform baptisms for their friends and family in the Endowment House.[90]

Was Brigham Young racist?

Yes. Brigham Young believed that Black people were inferior to white people,[91] described Black people with negative stereotypes,[92] and opposed marriages between Black and white people.[93]

Brigham also said, "we are all the children of one Father, whether we be . . . black or white"[94] and commended the example of Q. Walker Lewis, a Black elder.[95] He also spoke against the mistreatment of slaves, saying that "for their abuse" of enslaved people, "the whites will be cursed, unless they repent."[96]

Were Brigham's successors racist?

Yes. John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff accepted the idea that Black people are descended from Cain, Ham, and/or Canaan;[97] supported the priesthood ban;[98] and may have opposed interracial marriages.[99]

- Antone

“The Heavenly Father is the father of all races...” - Charlesetta C.

“Those were unfortunate and ignorant times! God forgive the injustice and disgusting acts of that time for they were or did not know what they do!” - Matthew

“While this topic has made a resurgence in recent times, I find it disappointing that many Latter-Saints continually try and justify Brigham Young's teachings. Brigham Young is not without sin, and it is important for us to root out racism.” - Eric

“We can look at Brigham Young and the early leaders. But what about in the 1900’s. My question is why did the church wait so long to allow black members full fellowship? Was it truly God denying them? I don’t think so. I think finally church leaders had to make a change.” - Nathan

“By some measures, even with the Priesthood ban, the Church was still very progressive with race. Life Magazine in 1904 created the Elder Berry with his Children comic, mocking the Church's diversity. Over time, things changed, and the Church needed to grow, hence 1978.”

about this topic

about this topic