D. Paul Sullins publishes research which refutes the claim from Blosnich(2020) that sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE) correlate with suicidality.

- Type

- Academic / Technical Report

- Source

- D. Paul Sullins Non-LDS

- Hearsay

- Direct

- Reference

D. Paul Sullins, "Sexual Orientation Change Efforts Do Not Increase Suicide: Correcting a False Research Narrative," Archives of Sexual Behavior 51 (2022): 3377–3393

- Scribe/Publisher

- D. Paul Sullins

- People

- D. Paul Sullins

- Audience

- N/A

- Transcription

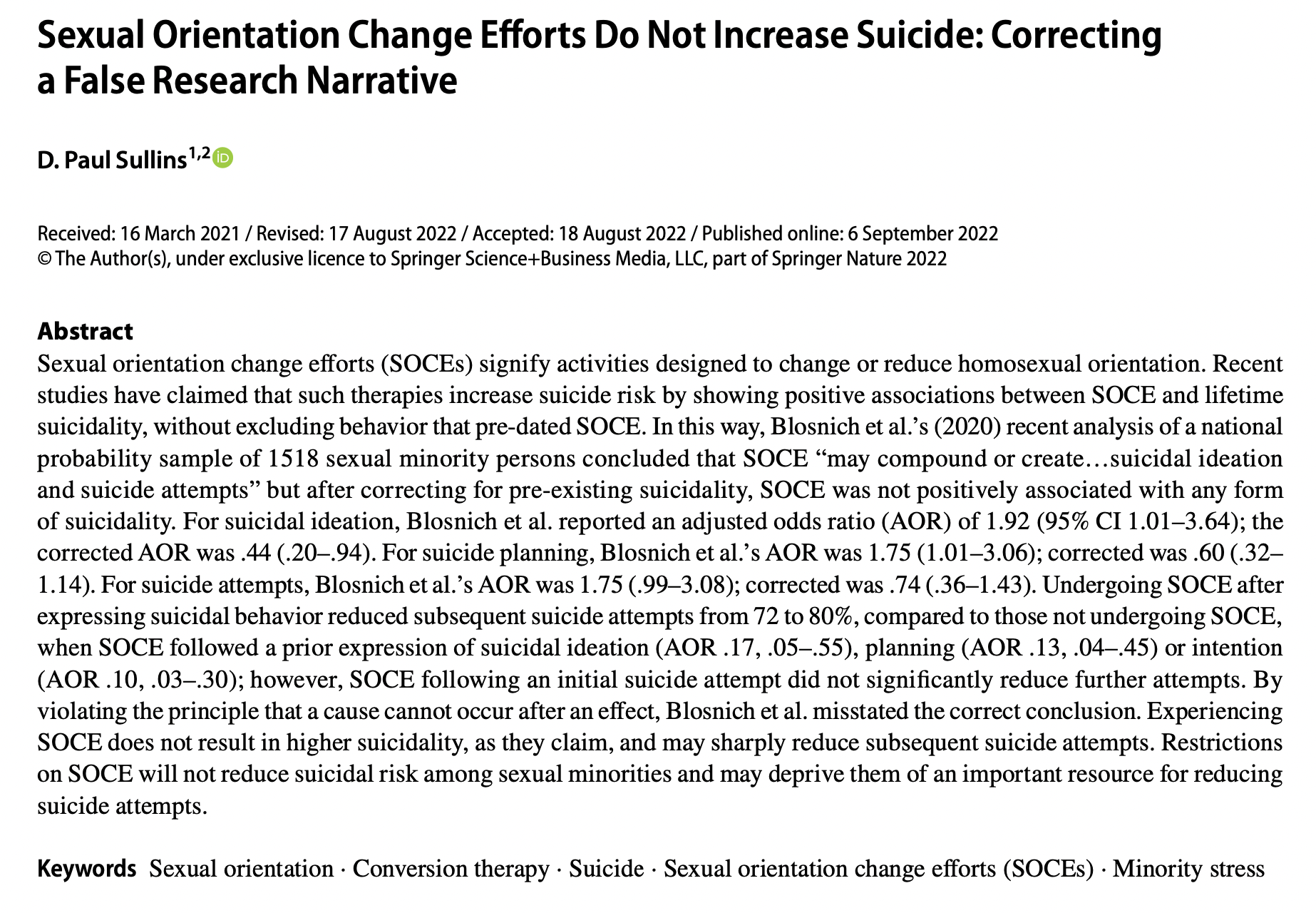

Sexual Orientation Change Efforts Do Not Increase Suicide: Correcting a False Research Narrative

D. Paul Sullins1,2

Received: 16 March 2021 / Revised: 17 August 2022 / Accepted: 18 August 2022 / Published online: 6 September 2022 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2022

Abstract

Sexual orientation change efforts (SOCEs) signify activities designed to change or reduce homosexual orientation. Recent studies have claimed that such therapies increase suicide risk by showing positive associations between SOCE and lifetime suicidality, without excluding behavior that pre-dated SOCE. In this way, Blosnich et al.’s (2020) recent analysis of a national probability sample of 1518 sexual minority persons concluded that SOCE “may compound or create...suicidal ideation and suicide attempts” but after correcting for pre-existing suicidality, SOCE was not positively associated with any form of suicidality. For suicidal ideation, Blosnich et al. reported an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 1.92 (95% CI 1.01–3.64); the corrected AOR was .44 (.20–.94). For suicide planning, Blosnich et al.’s AOR was 1.75 (1.01–3.06); corrected was .60 (.32– 1.14). For suicide attempts, Blosnich et al.’s AOR was 1.75 (.99–3.08); corrected was .74 (.36–1.43). Undergoing SOCE after expressing suicidal behavior reduced subsequent suicide attempts from 72 to 80%, compared to those not undergoing SOCE, when SOCE followed a prior expression of suicidal ideation (AOR .17, .05–.55), planning (AOR .13, .04–.45) or intention (AOR .10, .03–.30); however, SOCE following an initial suicide attempt did not significantly reduce further attempts. By violating the principle that a cause cannot occur after an effect, Blosnich et al. misstated the correct conclusion. Experiencing SOCE does not result in higher suicidality, as they claim, and may sharply reduce subsequent suicide attempts. Restrictions on SOCE will not reduce suicidal risk among sexual minorities and may deprive them of an important resource for reducing suicide attempts.

. . .

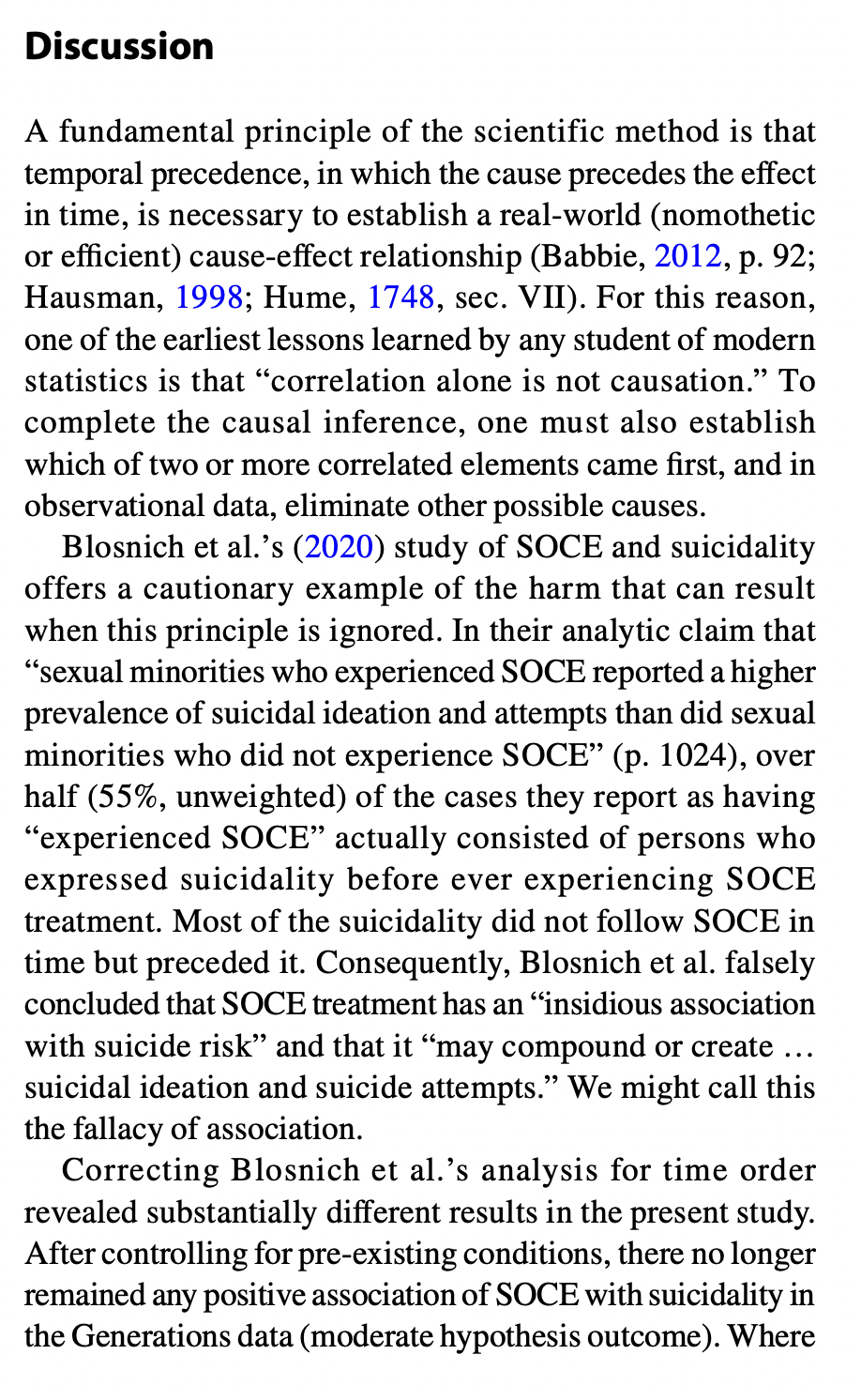

A fundamental principle of the scientific method is that temporal precedence, in which the cause precedes the effect in time, is necessary to establish a real-world (nomothetic or efficient) cause-effect relationship (Babbie, 2012, p. 92; Hausman, 1998; Hume, 1748, sec. VII). For this reason, one of the earliest lessons learned by any student of modern statistics is that “correlation alone is not causation.” To complete the causal inference, one must also establish which of two or more correlated elements came first, and in observational data, eliminate other possible causes.

Blosnich et al.’s (2020) study of SOCE and suicidality offers a cautionary example of the harm that can result when this principle is ignored. In their analytic claim that “sexual minorities who experienced SOCE reported a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempts than did sexual minorities who did not experience SOCE” (p. 1024), over half (55%, unweighted) of the cases they report as having “experienced SOCE” actually consisted of persons who expressed suicidality before ever experiencing SOCE treatment. Most of the suicidality did not follow SOCE in time but preceded it. Consequently, Blosnich et al. falsely concluded that SOCE treatment has an “insidious association with suicide risk” and that it “may compound or create ... suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.” We might call this the fallacy of association.

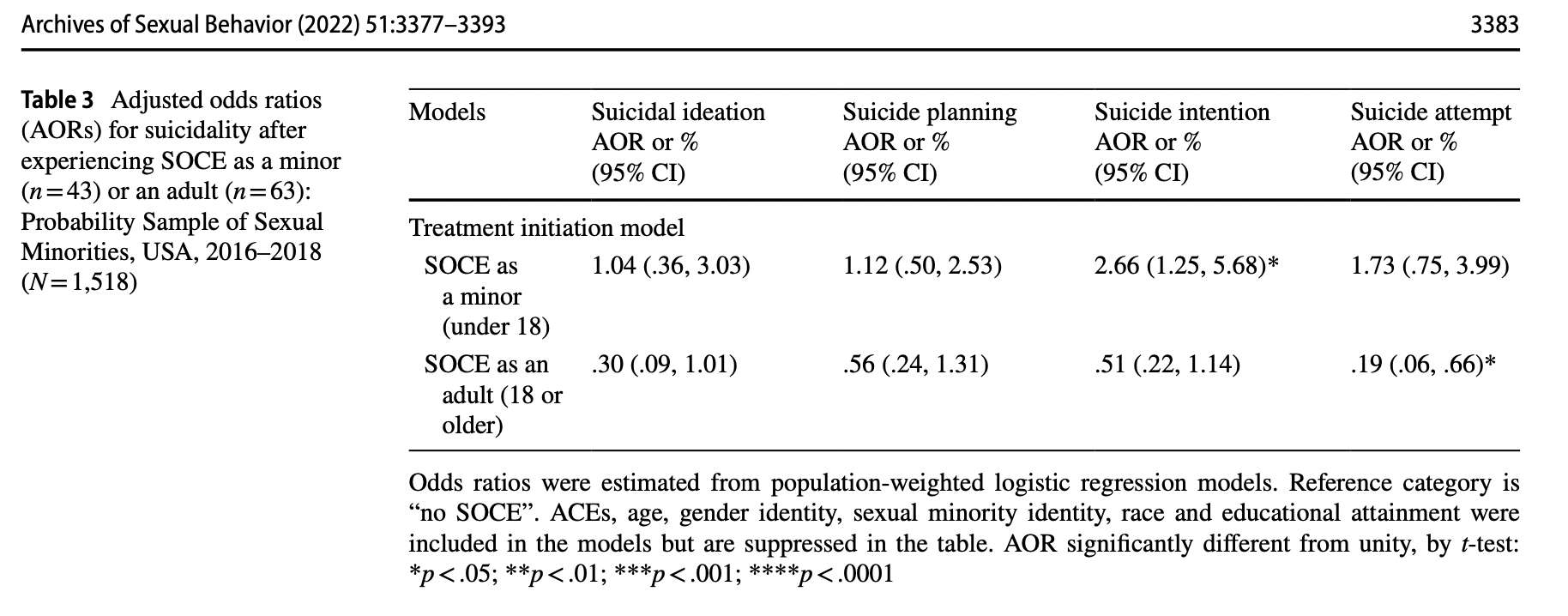

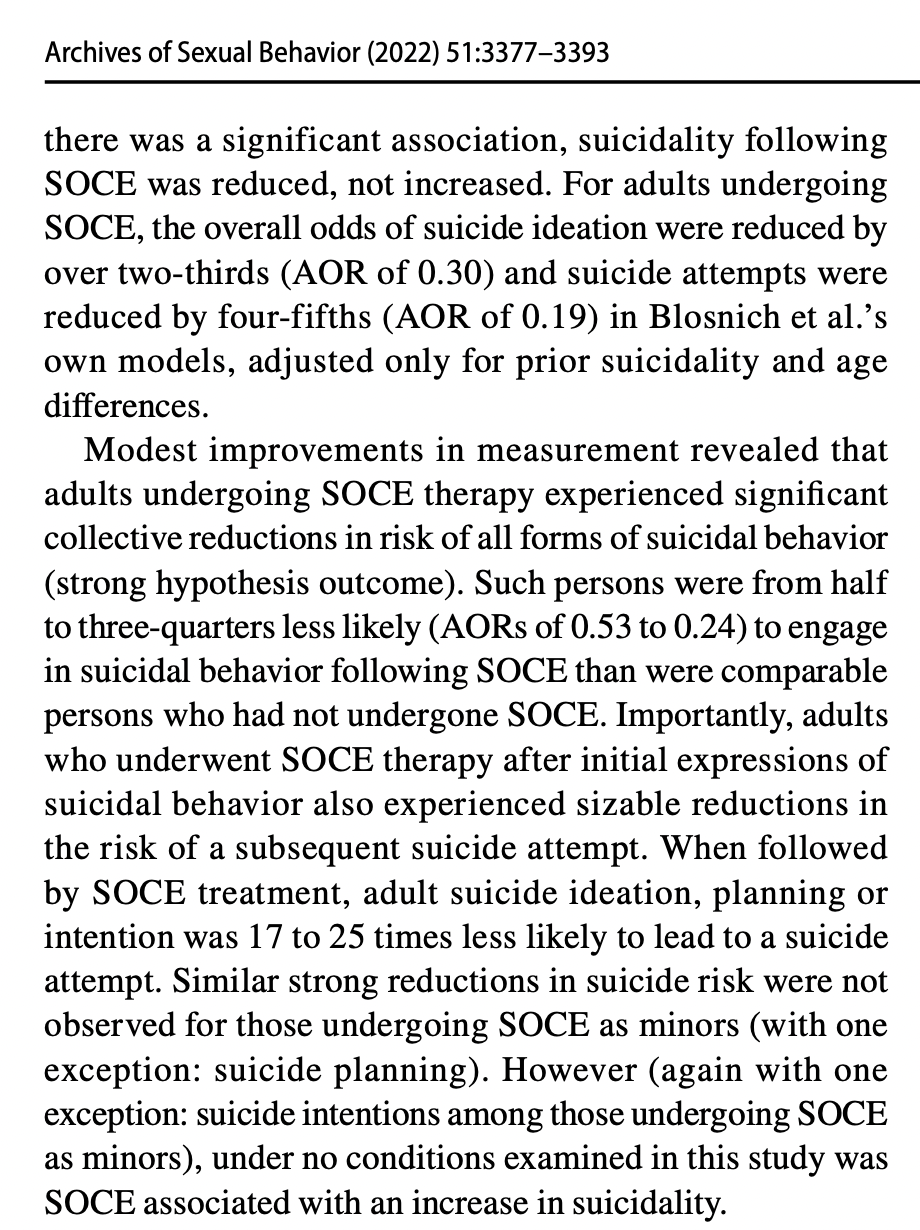

Correcting Blosnich et al.’s analysis for time order revealed substantially different results in the present study. After controlling for pre-existing conditions, there no longer remained any positive association of SOCE with suicidality in the Generations data (moderate hypothesis outcome). Where there was a significant association, suicidality following SOCE was reduced, not increased. For adults undergoing SOCE, the overall odds of suicide ideation were reduced by over two-thirds (AOR of 0.30) and suicide attempts were reduced by four-fifths (AOR of 0.19) in Blosnich et al.’s own models, adjusted only for prior suicidality and age differences.

Modest improvements in measurement revealed that adults undergoing SOCE therapy experienced significant collective reductions in risk of all forms of suicidal behavior (strong hypothesis outcome). Such persons were from half to three-quarters less likely (AORs of 0.53 to 0.24) to engage in suicidal behavior following SOCE than were comparable persons who had not undergone SOCE. Importantly, adults who underwent SOCE therapy after initial expressions of suicidal behavior also experienced sizable reductions in the risk of a subsequent suicide attempt. When followed by SOCE treatment, adult suicide ideation, planning or intention was 17 to 25 times less likely to lead to a suicide attempt. Similar strong reductions in suicide risk were not observed for those undergoing SOCE as minors (with one exception: suicide planning). However (again with one exception: suicide intentions among those undergoing SOCE as minors), under no conditions examined in this study was SOCE associated with an increase in suicidality.

. . .

- Citations in Mormonr Qnas

The B. H. Roberts Foundation is not owned by, operated by, or affiliated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.