University of Utah researcher Lisa M. Diamond states that 25-75% of sexual minorities report experiencing a change in sexual orientation at some point in their lives.

- Type

- Academic / Technical Report

- Source

- Lisa M. Diamond Non-LDS

- Hearsay

- Direct

- Reference

Lisa M. Diamond, "Sexual Fluidity in Male and Females," Current Sexual Health Reports 8 (2016): 249–256

- Scribe/Publisher

- Current Sexual Health Reports

- People

- Lisa M. Diamond

- Audience

- The Academy

- Transcription

Abstract

Sexual fluidity has been defined as a capacity for situation-dependent flexibility in sexual responsiveness, which allows individuals to experience changes in same-sex or other-sex desire across both short-term and long-term time periods. I review recent evidence for sexual fluidity and consider the extent of gender differences in sexual fluidity by examining the prevalence of three phenomena: nonexclusive (bisexual) patterns of attraction, longitudinal change in sexual attractions, and inconsistencies among sexual attraction, behavior, and identity. All three of these phenomena appear to be widespread across a large body of independent, representative studies conducted in numerous countries, supporting an emerging understanding of sexuality as fluid rather than rigid and categorical. These studies also provide evidence for gender differences in sexual fluidity, but the extent and cause of these gender differences remain unclear and are an important topic for future research.

. . .

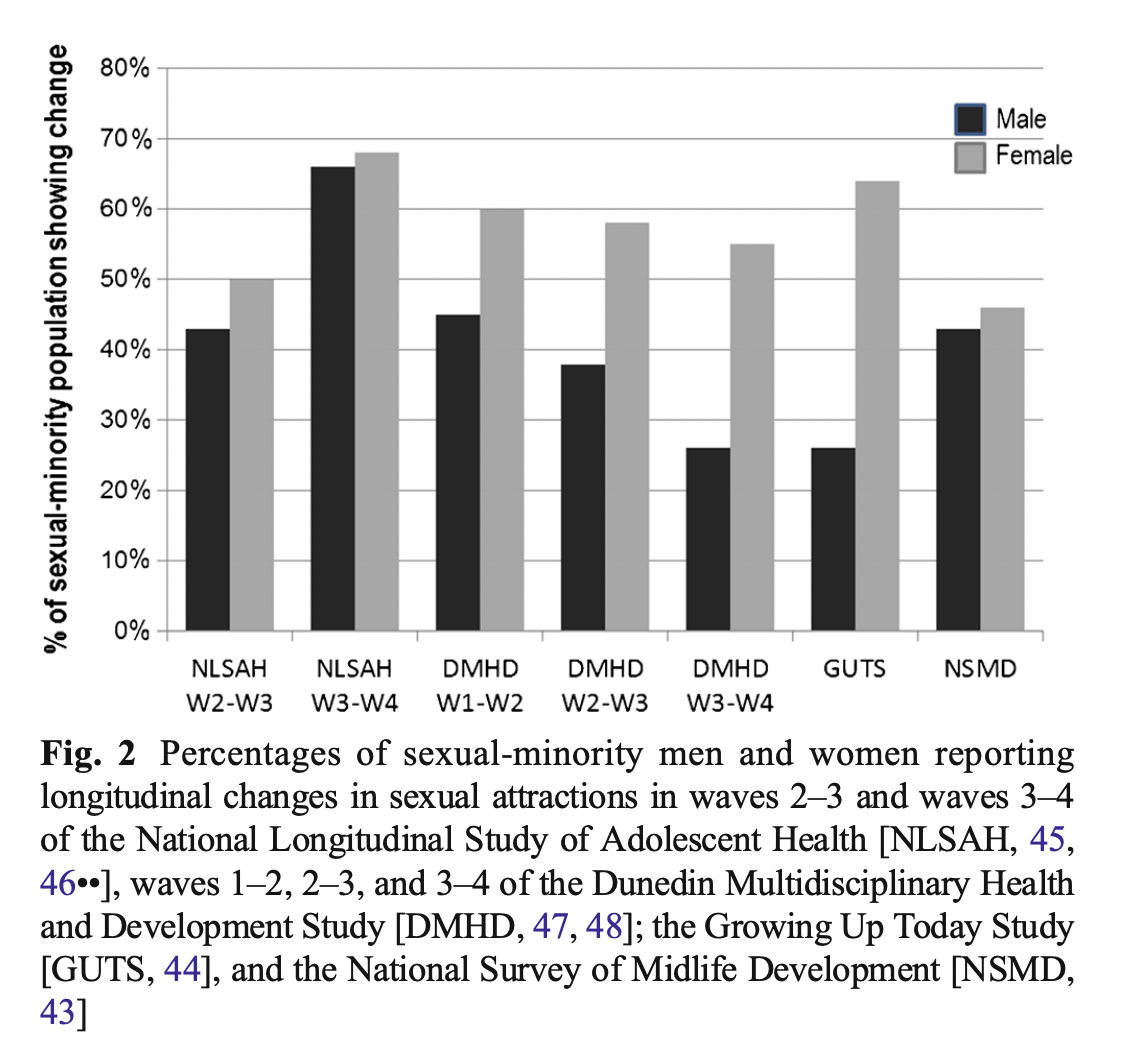

The other major conclusion that we can draw from these studies is that change in patterns of same-sex and other-sex at- traction is a relatively common experience among sexual minor- ities. Across the subgroups represented in Fig. 2, between 25 and 75 % of individuals reported substantial changes in their attrac- tions over time, and these findings concord with the results of retrospective studies showing that gay, lesbian, and bisexual- identified individuals commonly recall having undergone previ- ous shifts in their attractions [4•, 5]. Such findings pose a pow- erful corrective to previous oversimplifications of sexual orienta- tion as a fundamentally stable and rigidly categorical phenome- non [reviewed in 42•]. Yet the emerging body of longitudinal research does not suggest that women are uniformly more changeable than men, contrary to the notion of a global gender difference in sexual fluidity [2••, 28••]. Rather, the role of gender in predicting change varies for individuals who begin with dif- ferent patterns of attraction, and we have yet to understand how gender might interact with other potential predictors of change, such as age, relationship history, education, and social context.

Before leaving the topic of change, it is critically important to differentiate between the forms of change represented in Fig. 2, which can be described as unintentional change, and changes which result from individuals’ effortful attempts to eliminate their same-sex attractions in order to conform to social and religious norms which stigmatize and denigrate same-sex sexuality (known as sexual orientation change efforts). There is current- ly no evidence that therapeutic attempts to extinguish same-sex attractions are effective, and in fact these attempts have been found to cause psychological harm [reviewed in 50]. Whereas observational studies of naturally occurring change can reveal important information about the expression of sexuality of the life course, studies on effortful therapeutic change are primarily relevant for understanding the psychological consequences of the social privileging of heterosexuality over same-sex sexuality.

. . .

Conclusion

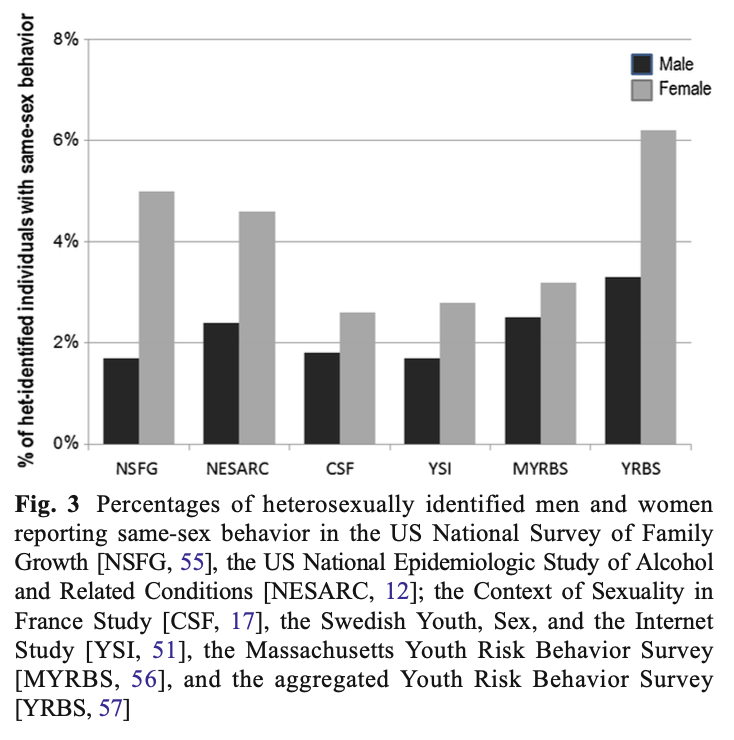

The existing body of international research assessing sexual attractions, behaviors, and identities among representative samples of adolescents and adults shows that sexual orienta- tion is not a static and categorical trait. Rather, same-sex sex- uality shows substantial fluidity in both men and women, and this fluidity takes a number of forms. It can be observed in the high rates of nonexclusive (i.e., bisexual) patterns of attraction among men and women; it can be observed in the fact that historical changes in social acceptance of same-sex sexuality have led to increases in the population prevalence of same-sex sexuality; it can be observed in the high numbers of sexual- minority men and women who show changes in their pattern of attractions over time, well into adulthood; it can be ob- served in the high numbers of men and women who flexibly engage in patterns of sexual behavior that do not concord with their self-described identity or attractions. Although the extant research suggests that all of these phenomena are somewhat more common in women than in men, it is difficult to draw reliable conclusions about the extent of gender differences in sexual fluidity, and the cause of such gender differences. Given that the most reliable gender difference appears to be the higher prevalence of nonexclusive attractions among women than men, one possibility is that this gender difference drives many of the other gender differences in indices of sex- ual fluidity (such as the likelihood of change in attractions over time, which appears to be greater among both men and women with nonexclusive versus exclusive attractions). Future longitudinal research that carefully examines indices of sexual fluidity among diverse and representative samples of women and men will help to elucidate the dynamic expression of same-sex and other-sex sexuality over the life course.

- Citations in Mormonr Qnas

The B. H. Roberts Foundation is not owned by, operated by, or affiliated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.