Native American Extermination Order

What was the Native American Extermination Order?

The "extermination order" was an order issued by Brigham Young[BIO] through Daniel H. Wells[BIO] on January 31, 1850, to stop “the operations of all hostile Indians and otherwise act as the Circumstances may require, exterminating such, as do not separate themselves from their hostile Clans, and sue for peace."[1]

Timeline

1847

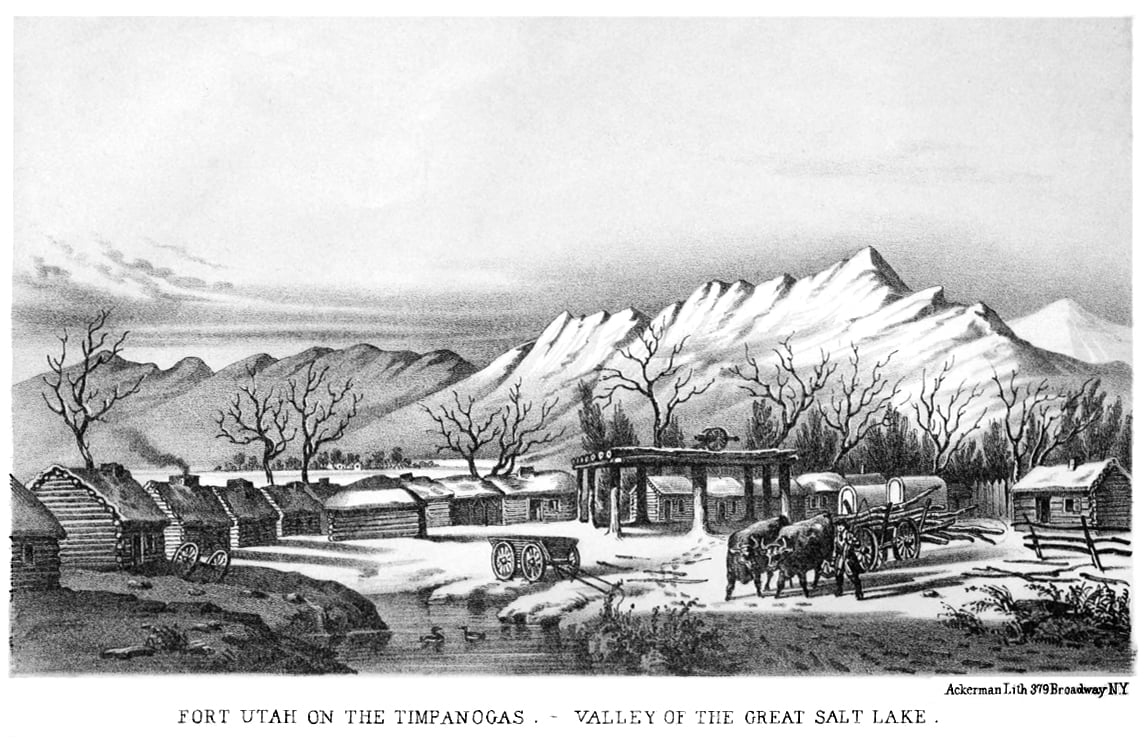

The first company of pioneers arrives in the Salt Lake Valley.[2]

February 1849

March 1849

March 1849

April 12, 1849

April 18, 1849

Brigham Young advises Utah Valley Saints to be "vigilant" with self-defense with the indigenous groups but to also focus on "teach[ing] them to raise grain" and "order[ing] them to quit stealing."[8]

October 15, 1849

January 8, 1850

Brigham Young advises Utah Valley Saints that "there is no necessity" for "warring with the Indians and killing them."[10]

January 31, 1850

January 31, 1850

February 4, 1850

February 13, 1850

February 18, 1850

Daniel H. Wells issues an order directing officials to "exterminate" all Native Americans that will not agree to "sue for peace."[15]

February 1850

Daniel H. Wells reports his success in expelling Native Americans from Peteetneet River (Creek) area in Payson Canyon to Brigham Young.[16]

February 28, 1850

Brigham Young explains to Orson Hyde that the "Utah Lake Indians" had "killed many of our brethren's cattle" and "shot at the brethren at Utah" until "self-defense demanded immediate action."[17]

Why did Brigham give the extermination order?

In a February 28, 1850 letter, Brigham Young explained that he ordered the militia to attack hostile Native Americans[19] because they had fired rifles at settlers and killed livestock.[20][21]

Brigham appealed to the United States military stationed at Fort Hall, Idaho, for help, but because of the distance and depth of the snow, Brigham was advised[22] to send the local militia accompanied by U.S. Officers.[23]

Before this order (and after), Brigham encouraged peace and restraint.[24]

What was the result of the order?

The militia[25] fought with Native Americans who were armed with rifles and bows[26] in the "Provo Bottoms"[27] and Payson Canyon.[28] About two dozen native combatants were killed in the Provo battle and at least one militia member was killed and several wounded.[29]

Native women and children were also brought to Salt Lake City, housed and fed for the winter, and returned to their lands in the spring.[30] Daniel Wells reported that Utah Valley was peaceful for two years afterward.[31]

Was this order meant to be a genocide?

No. The order resulted in two brief battles with relatively few causalities and prisoners were housed and fed and returned to their lands. According to Daniel Wells, there were more deaths after the battles due to the native prisoners "not being able to stand our way of living."[32]

The order used the word "exterminate" in this context: "Cooperate with the inhabitants of said valley in quelling and staying the operations of all hostile Indians and otherwise act as the circumstances may require exterminating such, as do not separate themselves from their hostile clans and sue for peace."[33]

So, maybe he didn’t order a mass killing, but Brigham Young was racist toward indigenous Americans, wasn’t he?

Yes, though his views seemed more condescending than hateful.[34] Brigham Young believed that indigenous Americans came from a common ancestry dating back to the Book of Mormon.[35]

Relations also varied from tribe to tribe: Young developed a friendly relationship with the Shoshone,[36] even as hostilities developed among the Ute Tribes.[37]

What guidance did Brigham Young give people on how to interact with the Native Americans?

Brigham Young generally advocated for peaceful coexistence[38] and considered peace with the Native Americans to be “hundreds and thousands of dollars cheaper” than warfare.[39]

When Utah Valley residents complained to Brigham about the thefts,[40] he directed them to avoid, where possible, violent conflicts with the natives.[41] Later, after a conflict between the settlers and the local indigenous groups,[42] Brigham also requested that the Saints "restore them[selves] their property, and make ample satisfaction of killing one of their tribe." [43]

Related Question

Did B. H. Roberts, a Church scholar, think that Native Americans were not descendants of Lehi?

Read more in B. H. Roberts's Testimony

How did Brigham's policy of peace work out in practice?

While Young urged moderation,[44] settlers faced ongoing conflicts,[45] so he deployed the territorial militia under circumstances that seemed unsolvable by diplomacy.[46]

Did Latter-day Saints ever ally themselves with Indigenous groups against other white Americans?

Sometimes. The Paiute tribe[BIO] allied with Latter-day Saints in the southern Utah settlements during the Utah War (1857) against U.S. federal troops.[47] A missionary to the Paiute tribe described them as the “battle ax of the Lord.”[48]

Did Church leaders meddle in native American politics?

Occasionally. For example, in the early 1850s, Commander Daniel H. Wells instructed "hostile" Utes to obey Black Hawk,[BIO] knowing that he was collaborating with Church leaders.[49]

In another example, Kanosh (sometimes spelled "Kenosh"),[BIO] the chief of Pahvants, joined the Church[50] and collaborated with Church leaders in Utah.[51]

Did the Church ever apologize or acknowledge its role in these conflicts?

Somewhat. Church Historian, Elder Marlin K. Jensen[BIO] urged Utahns to “acknowledge and appreciate the monumental loss” Utah’s Native American populations have experienced.[52] However, the Church has not released an official apology for the clashes between the indigenous groups and the settlers.

- Riley

“Everyone is unique and different in their own way. Some can reasoned with while others cannot. Some things are beyond anybody's control. All we can do is look at the past to better reform and sculpt our future.”

about this topic

about this topic