Black Saints and the Priesthood (1895–1978)

Events Related to Black Saints and the Temple and Priesthood Restriction Between 1895 and 1978.

Turn of the Century and Joseph F. Smith Era (1885-1915)

June 1885

January 27, 1895

August 22, 1895

January 2, 1902

March 16, 1904

April 9, 1905

President Joseph F. Smith states in General Conference that people "unfortunate enough not to be white" are sometimes "superior to many of their boasting white brothers."[7]

1907

April 19, 1908

"The Negro and the Priesthood" published by an unknown author in Liahona: The Elders’ Journal claims that Brigham Young taught that Blacks "did not possess sufficient innate spiritual strength" to hold the priesthood.[9]

August 26, 1908

President Joseph F. Smith states in a First Presidency meeting with the Twelve that any ordination of Black people to the priesthood must be "regarded as invalid."[10]

February 6, 1912

April 17, 1913

1915

Heber J. Grant and George Albert Smith Era (1918-1951)

1921

1924

The national Ku Klux Klan organization reports a strong increase in Utah membership despite "powerful opposition" from the Church.[15]

1931

December 14, 1931

January 25, 1940

January–June 1945

Elder Harold B. Lee gives a series of radio lectures and offers a "pre-existence" rationale for the priesthood ban—possibly representing the first proposal of the rationale.[21]

1947

July 17, 1947

October 9, 1947

A meeting of the First Presidency and Council of the Twelve considers a request by O. J. Umondak of Nigeria for missionaries to be sent to his country.[24]

October 9, 1947

November 3, 1947

In a letter to a BYU student, David O. McKay says he "know[s] of no other basis" for the restriction besides the Book of Abraham and that he believes the restriction "dates back to our pre-existent life."[27]

April 12, 1948

1949

The First Presidency produces a standard response to queries about the priesthood restriction to be used in personal correspondence which states that the restriction is not "policy," but a "direct commandment from the Lord."[30]

March 3, 1949

BYU student leaders write a letter to the BYU Universe student newspaper to protest racial discrimination.[31]

April 10, 1951

Summer 1951

Three apostles separately encourage Black Latter-days Saint Abner and Martha Howell to undertake a "mission" to Black members in various cities of the United States.[33]

David O. McKay Era (1951–1958), Desegregation and Discussion

June 17, 1952

January 31, 1953

Ernest L. Wilkinson states that David O. McKay told him that "the relationship of the Church to the colored person was one of the most pressing problems that had to be faced and resolved."[35]

January 1954

Church President David O. McKay lifts the requirement in South Africa for white Latter-day Saints to prove non-African genealogy prior to priesthood ordination.[36]

March 1954

Sterling M. McMurrin[BIO] reports that in March 1954,[37] President David O. McKay told him that the priesthood restriction "is a practice, not a doctrine," that "the practice will some day be changed," and that "there is no such doctrine" of the "divine curse" upon Blacks.[38] However, McMurrin also stated that McKay referenced the Pearl of Great Price as a "scriptural precedent" for the restriction.[39]

May 13, 1954

August 27, 1954

ca. 1954–56

President McKay reportedly approves previously-denied temple blessings for two siblings who were believed to have Black ancestry.[43]

1957

May 13, 1958

President McKay authorizes Fijians, the only group of Polynesians under restriction, for ordination to the priesthood.[46]

October 11, 1958

October 24, 1958

1958

David O. McKay Era (1959–1968), Civil Rights Controversies, Beginnings in West Africa

1960

March 9, 1960

March 23, 1960

November 10, 1960

February 24, 1961

President David O. McKay writes in his diary that the "only reason" for the priesthood restriction is found in the Book of Abraham.[56]

September 1961

In a letter to First Presidency members Henry D. Moyle[BIO] and Hugh B. Brown,[BIO] Stewart L. Udall,[BIO] a disaffected Latter-day Saint[57] and the US Secretary of the Interior, calls for the Church to clarify its position toward Black people.[58] In their response, Moyle and Brown refer to ideas about premortal origins for the priesthood restriction and interracial marriage.[59]

June 1962

July 14, 1962

Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith disputes the statement of Clare Boothe Luce about the Church's views on Black people and said her comments about George Romney's purported differences were based on a "false premise."[61]

January 11, 1963

March 5, 1963

June 7, 1963

Summer 1963

October 1963

October 6, 1963

In General Conference, Hugh B. Brown reads a public statement calling for the "establishment of full civil equality for all of God's children."[69]

December 13, 1963

February 14, 1964

1964

March 1965

After BYU grants scholarships to about a half dozen Nigerian students, Apostle Harold B. Lee voices opposition to the scholarship program because it "created a social situation at BYU."[74]

June 15, 1965

President David O. McKay decides that the Church should establish itself in Nigeria, "despite not being able to confer the priesthood."[75]

November 4, 1965

After prayerful discussions by the First Presidency and the Twelve[76] about LaMar Williams' mission to establish the Church in Nigeria, it is decided to call him home because "the time was not right."[77] Months later, a coup against the Nigerian government ignites a series of conflicts resulting in the Nigerian Civil War.[78]

August 1966

October 25, 1966

In a talk to BYU students, Ezra Taft Benson states that "there is nothing wrong with civil rights – it's what is being done in the name of civil rights that is shocking," referring to Martin Luther King, Jr.'s alleged involvement with Communism.[80]

1967–1970

May 1967

In an open letter, Latter-day Saint and U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Stewart L. Udall, calls publicly for the removal of the "restriction now imposed on Negro fellowship."[82] Spencer W. Kimball and Delbert L. Stapley[BIO] send letters to Udall expressing their disappointment in his attitude.[83][84]

September 29, 1967

In General Conference, Ezra Taft Benson denounces the civil rights movement as a "tool of Communist deception" but that "we must not place the blame upon Negroes."[85]

April 5, 1968

David O. McKay Era (1968–1969), Protests Target BYU, Church Statement on Civil Rights

April 13, 1968

November 1968

1968–1969

President McKay reportedly prays about the possibility of changing the priesthood restriction on several occasions during this period, but each time the answer was "not yet."[92]

March 27, 1969

After a year-long investigation, the Health, Education, and Welfare Office for Civil Rights concludes that BYU is "in compliance with" the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[93]

May 1969

According to the Daily Universe, BYU students plan events for a "Brotherhood Week" to increase understanding of racial issues and perform service for needy communities, but later university and Church directives "pretty much cut the heart out of the week."[94]

Fall 1969

October 17, 1969

October 23, 1969

In response to the incident involving fourteen University of Wyoming players, The Salt Lake Tribune reports that BYU student officers write and submit a statement on civil rights to the BYU administration.[99]

November 3, 1969

November 5, 1969

November 13, 1969

Stanford University announces that it will not schedule future athletic events with BYU because of the Church's priesthood restriction.[107]

November 30, 1969

BYU President Ernest L. Wilkinson records in his diary that he had a "very strong feeling" against the priesthood ban in a meeting with the Western Athletic Conference (WAC) university presidents.[108]

December 15, 1969

December 25, 1969

The Salt Lake Tribune reports First Presidency counselor Hugh B. Brown as saying that the priesthood restriction "will change in the not-too-distant future."[113]

Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold B. Lee Eras (1970-1973), BYU Protests End, Genesis Group Begins

1970

Stephen G. Taggart's book, Mormonism's Negro Policy, is published. It argues that the priesthood and temple restrictions originated with Joseph Smith and were triggered by local circumstances in the South.[114]

January–April 1970

The Black Student Union of the University of Washington launches a series of protests seeking to sever relations with BYU,[115] but the protests subside after the attorney general of Washington issues an opinion favorable to BYU.[116] Similar opinions were given in Wyoming and Utah, and a lawsuit against BYU was dismissed.[117]

ca. April 1970

BYU publishes full-page ads in various newspapers in Washington and Oregon stating that BYU accepted "any race, creed, color, or national origin."[118] BYU prepares and distributes a four-page information booklet that explains that the Church "is not racist" and that the priesthood restriction will someday be lifted.[119]

October 8, 1970

An editorial in the Tucson Daily Citizen reports that a University of Arizona committee that investigated BYU concluded that "BYU is no more racist than any other university" and recommended to the WAC that further demonstrations be suspended.[120]

November 25, 1970

December 1970

In Brazil, missionaries use lineage lessons to teach potential converts about the priesthood restriction and to determine the possibility of whether they are of African descent.[123]

May 23, 1971

In his diary, President Wilkinson records a meeting with the Western Athletic Conference (WAC) university presidents where it was decided that Arizona State cannot exclude BYU from the playing schedule due to the priesthood restriction.[124]

May 28, 1971

According to Edward Kimball, a general policy for Black Saints to receive patriarchal blessings is approved in 1971.[125]

October 19, 1971

President Joseph Fielding Smith approves the organization of the Genesis Group, an official Church body that provides support to Black Saints.[126]

July 1972

Harold B. Lee becomes president of the Church, and journalists from Newsweek, Los Angeles Times, and other publications speculate about the lifting of the priesthood restriction.[127]

Spring 1973

Late 1973

Spencer W. Kimball Era (1973 - June 9, 1978), Boy Scout Controversy, São Paulo Brazil Temple, Lifting of the Restriction

1973–1978

December 30, 1973

July 24, 1974

The Miami News and the New York Times report that the NAACP intends to sue the Boy Scouts because of a Church policy that discriminated against Black scouts by designating deacon's quorum presidents to be senior patrol leaders.[134]

November 1974

Church changes its policy of deacon quorum presidents serving as senior patrol leaders in the Boy Scouts, and the NAACP lawsuit is dismissed.[135]

1975

Volume 6 of James R. Clark's Messages of the First Presidency is published. None of the three First Presidency statements relating to the priesthood restriction up to this point were included in the compilation.[136]

March 1, 1975

April 3, 1976

June 1977

Bruce R. McConkie reports that President Kimball asked apostles to give him memos on the subject of the priesthood and temple restriction[141]

January 1978

March 1978

According to Edward Kimball, Church President Spencer W. Kimball goes to the temple to pray about the restriction and on March 23, he tells his counselors that his impression was "to lift the restriction on the blacks."[143]

April 20, 1978

President Kimball reportedly asks "the Twelve to join the presidency in praying that God would give them an answer. Thereafter he talked with the Twelve individually."[144]

May 4, 1978

LeGrand Richards reportedly sees President Wilford Woodruff in the Salt Lake Temple during a discussion of the priesthood restriction.[145]

June 1, 1978

June 9, 1978

During a meeting with all available General Authorities, an announcement of the lifting of the temple and priesthood restrictions is given to the press for public release.[148]

September 16, 1978

General Sunday School president Russell M. Nelson receives a dream wherein Harold B. Lee states that he would have received the same priesthood revelation as Spencer W. Kimball, had he remained living as prophet.[149]

What was the priesthood and temple ban?

From the early days of the Church until June 1978, Latter-day Saints of African heritage were specifically barred from holding the priesthood and participating in temple ordinances.[150]

The restriction was interpreted slightly differently at different times, including exceptions,[151] varying levels of strictness,[152] and the explicit removal of at least one ethnic group from the restriction.[153]

Was the modern, twentieth-century Church racist?

Yes. For most of the twentieth century, many in Church leadership voiced racist ideas and followed racist practices, specifically towards people of African descent.[154]

Was the Church more racist than American society at the time?

Probably not. In 1966, sociologist Armand L. Mauss conducted a survey of Latter-day Saints' "anti-Negro" attitudes and concluded that while there were some differences, there were "no systematic differences in secular race attitudes were found between Mormons and others or between orthodox and unorthodox Mormons."[155]

Did the Church ever segregate congregations?

No, there was never a policy of segregation, but there was at least one instance where a Black family in Ohio was asked to not attend Church by their local leadership.[156]

Abner Howell, a Black church member, also remembered Elder Stephen L Richards as saying if Black Saints "don't want to mingle with us, we'll build them a church of their own, like we have done the Spanish people here," in reference to Spanish-speaking congregations in some locations.[157]

Did the Church officially advocate for segregation in non-Church settings?

No. In 1969, the only official Church statement on the topic stated: "Each citizen must have equal opportunities and protection under the law with reference to civil rights . . . We have no racially-segregated congregations."[158]

However, individual Church leaders and members sometimes spoke in favor of segregation.[159][160] And, as in many other states,[161] segregation in housing[162] and public places[163] in Utah continued to prevail until the mid-1960s.[164]

Is it true that the Church segregated blood from Black donors at LDS Hospital until 1953?

Yes. Up until the early 1950s, it was the standard practice of the American Red Cross and other hospitals to segregate blood from Black persons,[165] even though conventional medical thought rejected that there was any distinction.[166]

The LDS Hospital also followed this practice, but possibly because there was a concern that a blood transfusion from a Black donor would make the recipient ineligible for priesthood office.[167]

Was there a policy to not teach Black people the gospel?

There was no official Churchwide policy to not teach Black people the gospel, but leaders often discouraged and sometimes prohibited[168] missionary work specifically targeting Black populations.[169][170]

Did the Church teach that less-valiant spirits in the "pre-existence" were assigned to Black bodies on earth?

Yes. While the idea was never official Church doctrine published in manuals or taught in General Conference, Church leaders offered it as an explanation personally and privately.

For example, in 1947 statements from the First Presidency made in private correspondence referred to premortal differences between individuals pre-mortal existence as an explanation for the priesthood ban.[171] And in 1958, Bruce R. McConkie's book titled Mormon Doctrine read, "Those who were less valiant in preexistence and who thereby had certain spiritual restrictions imposed upon them during mortality are known to us as the negroes."[172]

However, in 1961, President McKay recorded in his diary that the "only reason" for the priesthood ban was found in the Book of Abraham.[173] However, the pre-existence explanation persisted among some apostles[174] and also appeared in general terms within a 1969 First Presidency statement.[175]

Did other colleges refuse to play BYU sports teams because of the priesthood ban?

Yes. In April 1968, Black athletes at the University of Texas El-Paso were the first of several schools that called for boycotts of games with BYU.[176] BYU responded by publishing a statement at the Western Athletic Conference meeting in November of 1969 that said that there was no policy of racial discrimination at BYU.[177]

Did anything change as a result of protests against BYU in 1968–69?

Yes. BYU leadership reviewed and published its position on minorities and civil rights,[178] the University of Arizona published the results of its investigation of racism at BYU,[179] and the Office of Civil Rights issued a statement of review for BYU's compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[180]

Did the Church ever make any statements related to civil rights legislation?

Yes. On December 15, 1969, Hugh B. Brown[BIO] and N. Eldon Tanner,[BIO] the First and Second Counselors in the First Presidency, signed a statement supporting full civil rights for all citizens.[181]

Why didn't President McKay sign the statement about civil rights?

At that time, President McKay was in poor health and Church leaders had decided he would be excused from signing for the First Presidency on "all correspondence," so the statement was signed by his two counselors.[182]

Did the Church say in 1969 that the priesthood ban would soon be lifted?

The December 25, 1969 edition of The Salt Lake Tribune reported Hugh B. Brown, who was the First Counselor in the First Presidency, saying that the priesthood ban "will change in the not-too-distant future."[183] Brown said no more on the matter prior to the death of President McKay in January.[184]

What is the Genesis Group and how did it start?

The Genesis Group is an official Church body that provides support for Black members of the Church and has met at least monthly for many years.[185][186]

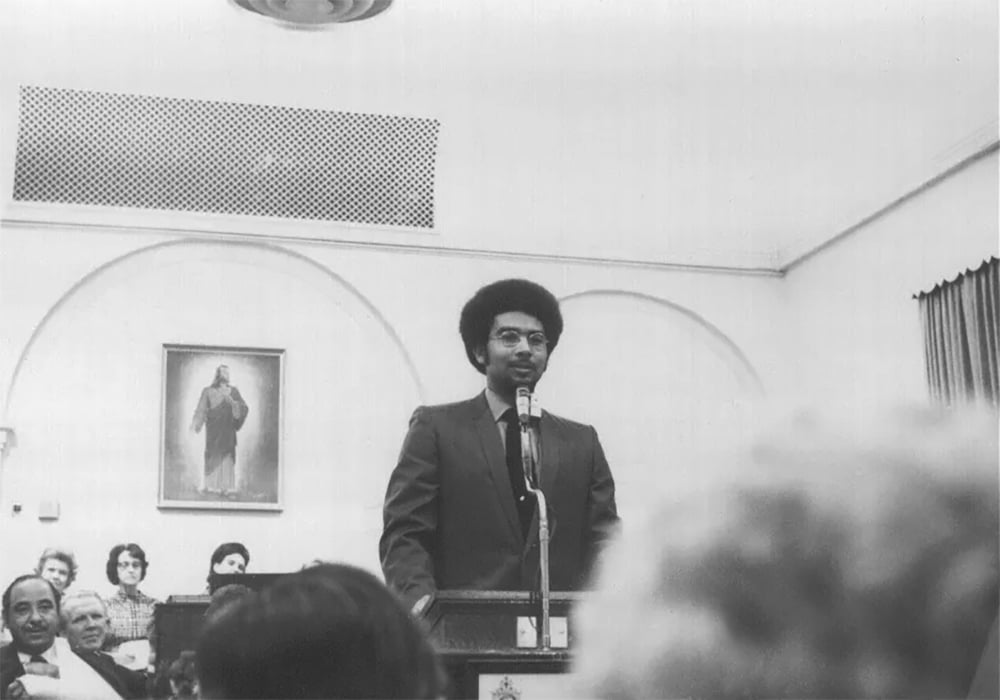

The Genesis Group was organized on October 19, 1971, at the request of Black Latter-day Saints Ruffin Bridgeforth,[BIO] Darius Gray,[BIO] and Eugene Orr.[BIO][187]

Was the priesthood and temple ban a policy or based on doctrine?

Church leaders consistently taught that the restriction was based on "doctrine,"[188] but in March 1954, David O. McKay reportedly said that the restriction was "not a matter of doctrine. It is simply a practice."[189] However, he was also reported to have said that there was "scriptural precedent" for the policy and that a change would require a revelation.[190]

Additionally, in 1973, Spencer W. Kimball said, "We are under the dictates of our Heavenly Father, and this is not my policy or the Church’s policy."[191]

Twentieth-Century Documents from the First Presidency Relating to the Priesthood and Temple Ban

Date | Document | Comments |

July 17, 1947 | Private letter to Lowry Nelson[BIO] | The First Presidency defends and explains the restriction in terms of events and doctrines relating to premortal life.[192] |

1949 | Private correspondence | The First Presidency invokes similar language about the premortal life as it did in 1947 while adding statements by Brigham Young and Wilford Woodruff.[193] |

August 17, 1951 | Private correspondence | This expanded version of the 1949 letter appends a "few known facts" about premortality.[194] |

October 6, 1963 | Official, public statement | The statement does not refer to the priesthood ban, but calls for "the establishment of full civil equality for all of God's children."[195] |

December 15, 1969 | Official, public statement | The statement argues on behalf of "civil rights and Constitutional privileges" for all people, references the pre-existence,[196] but says that the reasons for the priesthood restriction are not "fully known to man."[197][198] |

June 8, 1978 | Official Declaration 2 | The statement lifts the restriction without explanation except to say the decision to do so was confirmed "by revelation."[199] |

Are any presidents of the Church reported as having prayed about lifting the priesthood ban and being told by God not to do it?

Yes, although there are no firsthand reports available except from President Kimball.[200] (See table below.)

Reports of Presidents of the Church Seeking Revelation About the Priesthood Ban

Date | President | Account |

1954 | David O. McKay | Church historian Leonard J. Arrington[BIO] heard Elder Adam S. Bennion[BIO] report that as President McKay had studied and discussed the ban with the Twelve over the previous months, he "pled with the Lord" but was told the time was "not yet ripe."[201] |

1960s | David O. McKay | Historian Gregory Prince[BIO] reported President McKay's daughter-in-law as saying that she thought "it is time for a new revelation." President McKay replied, "So do I."[202] |

1960s | David O. McKay | Historian Gregory Prince related that a secretary in President McKay's office heard him say that he had "inquired of the Lord several times" but was told "not yet."[203] |

late 1960s | David O. McKay | President McKay reportedly told Elder Marion D. Hanks, "I have prayed and prayed and prayed, but there has been no answer."[204] |

1968–1969 | David O. McKay | Richard Jackson,[BIO] a Church architect, recalled David O. McKay's saying that after recent praying about the ban he was finally told by the Lord to "leave the subject alone."[205] |

1972–1973 | Harold B. Lee | Church historian Leonard J. Arrington was told that President Lee spent "three days and nights [of] fasting in the upper room of the temple . . . but the only answer he received was 'not yet.'"[206] |

1961–1976 | Spencer W. Kimball | President Spencer W. Kimball stated that he had "been praying about it for fifteen years without an answer."[207] |

Did President Kimball give any indication that the restriction would be lifted when he became president of the Church?

Shortly after he became President of the Church he said that he had given it "a great deal of thought and prayer"—that "the day might come when [Black men] would be given the priesthood, but that day has not come yet. Should the day come it will be a matter of revelation."[208]

Why was the revelation not received earlier?

It's unclear. President Kimball acknowledged that the question had repeatedly been brought before previous presidents of the Church,[209] but gave no reason for the delay except that it had to come when the Lord wanted it "and not until."[210]

Did the ban change because of social pressure?

Yes, it was probably a factor.[211][212] For example, in 1969 and 1970, several schools boycotted BYU sports over the priesthood restriction,[213] and in 1970, the IRS announced that the tax-exempt status of private schools would be revoked based on racial policies.[214]

However, according to emeritus BYU law professor Edward Kimball[BIO] by 1978 the "external pressure was the lowest it had been for years."[215]

Did the ban change because the Church built a temple in Brazil, which was home to many members of African descent?

Yes, it was probably a factor.[216] Brazil was known as the "land of racial democracy"[217] and was home to millions of descendants of enslaved Africans who had children with European colonists, which, according to J. Reuben Clark, made it "very difficult if not impossible" to determine genealogical lineage in Brazil.[218]

Church leaders observed that Afro-Brazilians had been contributing to the São Paulo temple; however, the policy was to bar from entry Brazilians with African ancestry.[219]

Has the Church given an official explanation for why the ban happened?

Sort of. While there has never been an official Church-wide statement with an explanation, individual Church leaders have responded to questions in writing, using official Church stationary, with explanations for the ban.[220]

The only official public statement on the ban before it was lifted was in 1969, but it did not offer an explanation except to say that it "extend[ed] back to man’s pre-existent state."[221]

In 2013, the Church published an essay disavowing "theories advanced in the past" about the restriction but did not provide an official explanation either.[222]

Related Question

Did Joseph Smith ever implement a policy to restrict Black members of the Church from the priesthood and temple ordinances?

Read more in Black Saints and the Priesthood (Joseph Smith era)

Isn’t this something the Church should know?

Probably.

What do most Latter-day Saints think about the priesthood restriction?

There is very little data available on this topic, but a survey from 2016 indicated that 4 out of 5 Church members believed that the ban was inspired by God.[223]

Simplified table of positions related to the priesthood restriction

Theories related to the Priesthood restriction | Theories related to God's involvement | Implication |

Church leaders implemented the restriction because of racist traditions and there was no authentic revelation or doctrine to justify it.[224] | God corrected this in 1978. |

|

God sustained this as a punishment until 1978.[225] | ||

God was not involved in the implementation or removal of the restriction. | ||

The restriction was inspired by God as a temporary practice for some wise purpose.[226][227] | God inspired the implementation[228] and the removal of the restriction.[229][230] |

What do we know about how the 1978 revelation was received?

It appears that individual spiritual confirmations were received during the prayer by each person present (see table below). Elder McConkie said that these confirmations were significant because "The Lord wanted independent witnesses who could bear record that the thing had happened."[234]

Comments from the First Presidency and Apostles about the 1978 revelation

| Source | Comments |

Spencer W. Kimball[BIO] | "I felt an overwhelming spirit there, a rushing flood of unity such as we had never had before."[235] President Kimball is also reported as having authored the following account in 1980: "The voice of God, given by the power of His Spirit, ‘the still small voice, which whispereth through and pierceth all things’ (D&C 85:6) made manifest that the Holy Priesthood, all of the blessings of the temple, including celestial marriage, together with all the obligations that appertain thereto, should now be offered, on the sole basis of personal worthiness, to all men of every race and color. On that sacred occasion, akin to certain Pentecostal days of old, each of the apostolic witnesses then present came to know the mind and will of the Lord relative to the salvation and exaltation of myriads of His mortal children."[236][237] |

Marion G. Romney[BIO] | "I am not just a supporter of this decision. I am an advocate."[238] |

N. Eldon Tanner[BIO] | The events surrounding the revelation are not described in Tanner's biography, but at the following conference, he was designated by President Kimball to present Official Declaration 2 for a sustaining vote.[239] |

Ezra Taft Benson[BIO] | “Following the prayer, we experienced the sweetest spirit of unity and conviction that I have ever experienced.”[240] |

Mark E. Petersen[BIO] | Petersen, who was on assignment in South America at the time of the prayer confirming the priesthood revelation, said: "I was delighted to know that a new revelation had come from the Lord."[241] |

Delbert L. Stapley[BIO] | Stapley, who was hospitalized at the time of the prayer confirming the priesthood revelation, sustained the action by saying, "I'll stay with the Brethren on this."[242] |

LeGrand Richards[BIO] | Richards, who had earlier reported having seen Wilford Woodruff in the room during a discussion of the priesthood restriction,[243] said that, within a prayer circle, they prayed "that the Lord would give us the inspiration that we needed to do the thing that would be pleasing to Him and for the blessing of His children."[244] |

Howard W. Hunter[BIO] | "Powerful witness of the Spirit . . . this confirmed the divine origin of the revelation.”[245] |

Gordon B. Hinckley[BIO] | “It was marvelous, very personal, bringing with it great unity and strong conviction that this change was a revelation from God.”[246] |

Thomas S. Monson[BIO] | "It was a source of great comfort to the Brethren to hear [President Kimball's] humble pleadings as he sought guidance in his lofty calling."[247] "We all knew and felt it was time."[248] |

Boyd K. Packer[BIO] | "During the prayer all present became aware what the decision must be."[249] |

Marvin J. Ashton[BIO] | “The most intense spiritual impression I’ve ever felt.”[250] |

Bruce R. McConkie[BIO] | "It was during this prayer that the revelation came. The Spirit of the Lord rested mightily upon us all."[251] |

L. Tom Perry[BIO] | “While he was praying we had a marvelous experience. We had just a unity of feeling. The nearest I can describe it is that it was much like what has been recounted as happening at the dedication of the Kirtland Temple. I felt something like the rushing of wind."[252] "We were not alone."[253] |

David B. Haight[BIO] | “The Spirit touched each of our hearts with the same message in the same way. Each was witness to a transcendent heavenly event.”[254] |

Did anyone oppose the lifting of the restriction in 1978?

President Kimball reportedly received about 30 letters of complaint, "nearly all from non-Mormons," calling him a "fraud" or "a traitor to his race."[255] The Salt Lake Tribune published a statement from Joseph LaMoine Jenson,[BIO] representing the Apostolic United Brethren,[256] that condemned the Church for lifting the priesthood restriction.[257]

How did Church members generally react to lifting the restriction?

Reportedly, members worldwide were almost universally positive.[258] “I shouted for joy,” said Monroe Fleming,[BIO] a Black resident of Salt Lake City and Latter-day Saint since 1956.[259]

After the announcement, when did Black saints begin to receive the priesthood?

Ordinations began almost immediately after the June 8, 1978 announcement of the revelation.[260] Joseph Freeman, Jr.[BIO] reportedly became the first Black man to receive the Melchizedek Priesthood in modern times,[261] and Genesis Group president Ruffin Bridgeforth[BIO] may have been the first to be ordained a high priest.[262]

- Jeffrey S.

“While a missionary in California(1970). taught a family that had adopted a black girl. We wrote the Prophet, Joseph F. Smith and asked if the little girl could be sealed to her parents. M. President received a letter from the First Pres. approving. They were baptized&sealed.” - Bryan

“Incredible work bringing this extensive amount of information together. Thank you for doing it.”

about this topic

about this topic