Black Saints and the Priesthood (Post 1978)

Timeline of Black Saints and the Priesthood after June 10, 1978

1978–1980

June 1, 1978

The First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles receive a revelation to end the priesthood ban.[1]

June 9, 1978

The end of the priesthood and temple restrictions is officially announced.[2]

June 11, 1978

June 13, 1978

The Salt Lake Tribune reports that President Spencer W. Kimball said that the revelation that prompted Official Declaration 2 was a "personal thing."[4]

June 18, 1978

A Church spokesperson gives a statement discouraging mixed-race marriages.[5]

1978

1978

July 4, 1978

July 23, 1978

August 18, 1978

August 28, 1978

September 16, 1978

September 28, 1978

September 30, 1978

Official Declaration 2, which extends priesthood and temple blessings to all worthy male members of the Church, is accepted in general conference.[17]

October 23, 1978

President Kimball gives a detailed description of the events surrounding the revelation on the priesthood at a mission conference in South Africa.[18]

October 24, 1978

October 30, 1978

President Kimball dedicates the São Paolo Brazil Temple.[21]

November 21, 1978

1981–1990

August 9, 1981

The Soweto, South Africa branch is established with racially integrated leadership during apartheid.[23]

April 1983

August 24, 1985

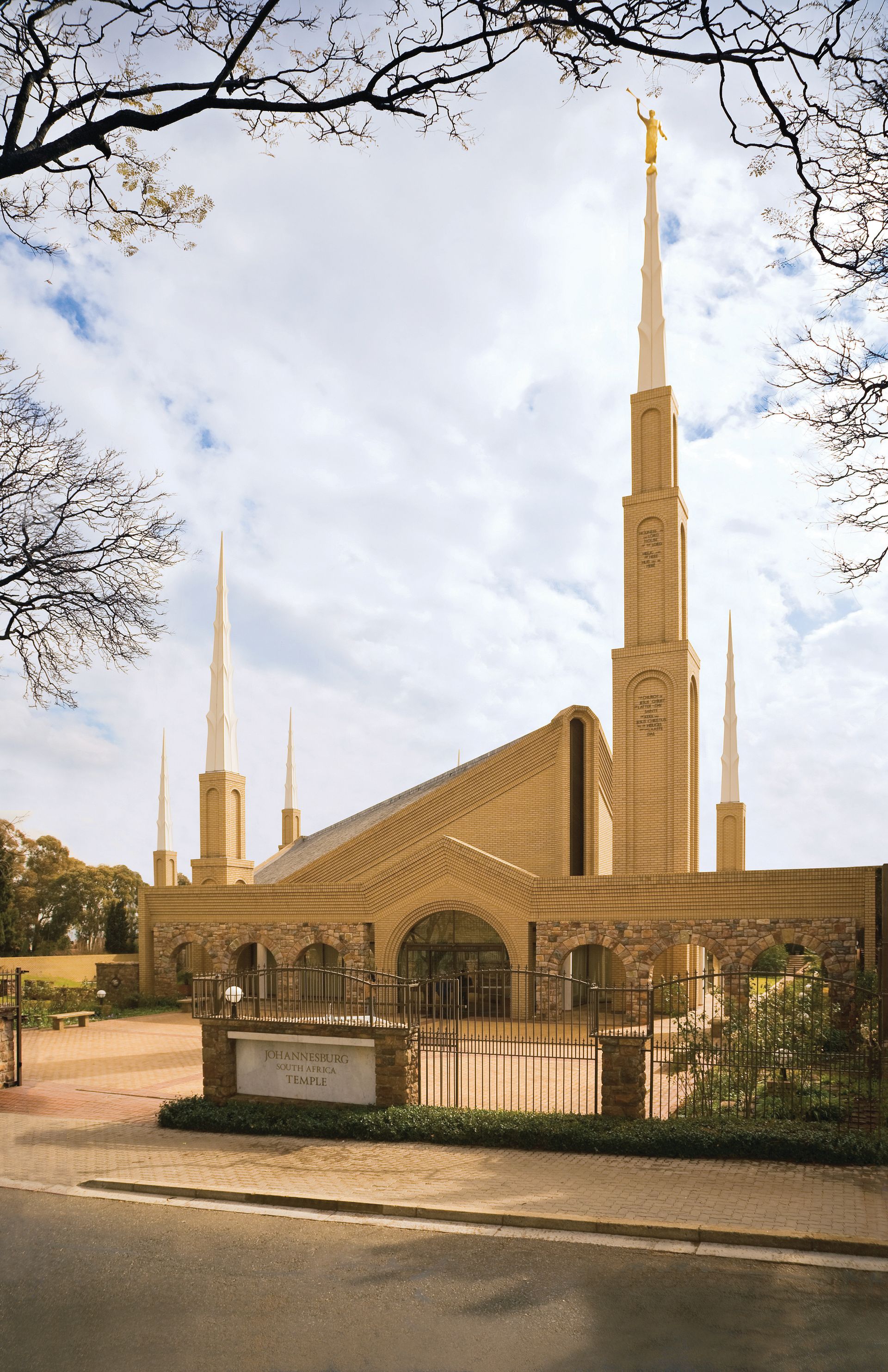

The first Latter-day Saint temple in Africa is dedicated in Johannesburg, South Africa.[25]

September 22, 1987

May 15, 1988

The first African stake outside of South Africa is organized in Aba, Nigeria.[27]

May 15, 1988

Church president Gordon B. Hinckley says that the June 1 revelation was received by the "voice of the Spirit."[28]

June 1988

Associated Press interviews Elder Dallin H. Oaks and Neal A. Maxwell on the tenth anniversary of the lifting of the priesthood restriction.[29]

June 1989

The government of Ghana bans the activities of the Church, closing chapels and ordering non-Ghanaian Saints to leave the country during a period known as "The Freeze."[30]

April 1990

November 1990

"The Freeze" in Ghana ends, and the Church returns to full activity in the country.[32]

1991–2000

May 1998

1999

2001–2010

April 5, 2001

A Church spokesperson denies the claim that the priesthood revelation was given in response to threats about the Church's tax-exempt status.[37]

2002

January 11, 2004

The first temple in Ghana (and the second temple in Africa) is dedicated.[41]

April 2006

In the priesthood session of general conference, President Gordon B. Hinckley states that "racial strife still lifts its ugly head" and that "there is no basis for racial hatred among the priesthood of this Church."[42]

April 30–May 1, 2007

January 19, 2008

The film Nobody Knows: The Untold Story of Black Mormons debuts as the first documentary on the history of the priesthood ban.[44]

June 8, 2008

The Church hosts a celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of the 1978 priesthood revelation.[45]

2011–2020

February 28–29, 2012

2013

A paragraph is added to Official Declaration 2 in the new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants that gives outlines some of the history around the priesthood restriction and affirms that "all are alike unto God."[48]

December 6, 2013

2014

2014–2015

2016

August 13, 2017

May 17, 2018

May 17, 2018

June 1, 2018

June 11, 2018

Jana Riess reports in her 2016 Next Mormons Survey that most Latter-day Saints in the United States still believe the priesthood and temple ban was "inspired of God and was God's will for the Church until 1978."[64]

October 31, 2018

June 1, 2020

October 3, 2020

In a general conference talk just prior to the United States presidential election, President Dallin H. Oaks denounces racism and lawlessness and encourages love and respect among all people.[68]

October 27, 2020

After speaking at a BYU devotional, Dallin H. Oaks makes national headlines for stating, "Black Lives matter!"[69]

November 16, 2020

Fifty-one years after 14 Black University of Wyoming football players protested BYU's racial restrictions, the first of several deliveries to food banks is made as a joint effort of Black 14 Philanthropy and the Church.[70]

2021–2025

February 25, 2021

The BYU Committee on Race, Equity, and Belonging releases a 64-page report that concludes, “Current systems at the university are inadequate for coordinating services for students seeking assistance with challenges related to race.”[71]

June 14, 2021

Collaborating with the First Presidency and NAACP leadership on a mutual learning and service initiative, the Church commits $2 million annually for three years to the NAACP to promote service and self-reliance.[72]

August 23, 2021

BYU announces the formation of a new Office of Belonging to address the needs "of all marginalized individuals on campus."[73]

October 23, 2021

The Genesis Group celebrates its fiftieth anniversary in the Salt Lake Tabernacle and restates the importance of its ongoing mission.[74]

2022

February 6, 2022

April 2022

A group of BYU students calling themselves the Black Menaces receives nationwide attention for their TikTok videos calling out racism and LGBTQ discrimination at BYU.[77]

July 22, 2022

August 28, 2022

September 9, 2022

2023

2024

Matthew L. Harris publishes Second-Class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality.[86]

March 19, 2025

The Church releases a new gospel topic essay about the Church and race.[87]

How did the priesthood and temple restrictions on Latter-day Saints of African descent end?

In June 1978, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles announced they had received a revelation while fasting, praying, and counseling together in the temple.[88] This revelation ended the priesthood and temple restrictions.[89]

The official announcement was canonized as Declaration 2 in the Doctrine and Covenants.[90] While President Spencer W. Kimball[BIO] did not share a written revelation like those found in the Doctrine and Covenants, the apostles involved testified that the end of the ban came through revelation.[91]

Why wasn't the written revelation behind Official Declaration 2 published?

It's unclear. In response to a similar question, the Salt Lake Tribune reported that President Kimball said that the revelation was a "personal thing."[92]

When it was removed, did the Church announce an official explanation for the original restriction?

No. Official Declaration 2 states that earlier prophets had promised an eventual end to the ban, but it does not address why there was a ban to begin with.[93]

Later, in the 2013 "Race and the Priesthood" essay, the Church disavowed various "theories advanced in the past" that were sometimes used as rationales for the ban,[94] but neither it nor future publications explained why the ban was put in place.[95]

Related Question

Has the Church given an official explanation for why the ban happened?

Read more in Black Saints and the Priesthood (1895–1978)

How did members of the Church react to the lifting of the priesthood ban?

Response varied. Many Latter-day Saints welcomed and celebrated the end of the priesthood ban.[96] Joseph Freeman,[BIO] the first ordained Black Latter-day Saint, described feeling an overwhelming mix of joy, gratitude, humility, and sacred responsibility as he finally received the priesthood.[97]

In the days following the revelation, President Kimball received "about thirty negative letters," according to his son Edward.[BIO][98] Most of the opposition came from former members who were affiliated with fundamentalist groups.[99]

Didn't the Church lift the ban because of social pressure?

No, probably not. The Church had faced social pressure.[100] However, President Kimball and members of the Quorum of the Twelve each testified they had received a revelation to lift the restrictions.[101]

Did the Church issue an apology for the priesthood restriction?

No. In the 1990s, some leaders reportedly considered issuing a "public repudiation" of the priesthood restriction.[102] Word of the effort leaked to the press,[103] and President Gordon B. Hinckley[BIO] distanced the Church from the effort.[104]

What does the Church say about the restriction now?

Over the last few decades, the Church has released the 2014 Race and the Priesthood essay,[105] the 2018 “Be One” celebration,[106] and the 2025 update to the essay series.[107] They condemn racism and emphasize that all are alike unto God.[108]

What have Church adjacent sources said about the origin of the ban?

In 2023, Deseret Book published a short book by historian W. Paul Reeve[BIO] that asserts the ban was not inspired by God.[109] That same year, Deseret Book also published a book with an excerpt from Elder Ahmad Corbitt,[BIO] who said that analysis to "assign blame" for the restriction is a "distraction" and that Jesus would say "neither have my Black children sinned, nor the prophets, but that the power of God should be made manifest."[110]

So what happened after the restriction was lifted?

Black men started being ordained almost immediately,[111] and the Church began announcing and building temples in Brazil and Africa.[112]

However, there are still many challenges for Black Saints,[113] even as the Church continues to work with the community.[114]

What are some of the challenges that Black Latter-day Saints have faced since the revelation?

Reports of continued racism among members[115] prompted repeated condemnations by Church leaders.[116] In West Africa, handbook instructions sometimes collided with traditional religious practices cherished by Church members.[117]

Student-organized groups such as the Black Menaces[BIO] and official organizations such as the BYU Office of Belonging[BIO] were created partly because people felt concerns of Black students were not being addressed.[118]

How did the revelation affect the growth of the Church?

Missionary work began to accelerate in Brazil and Africa in the months following the revelation.[119] By 2020, people of African descent made up an estimated 8% of the global membership of the Church.[120]

In 2022, it was reported that Africa, Brazil, the Philippines, and Central America were among the fastest-growing areas for the Church.[121] As of April 2023, there are more than twenty temples planned or built in Africa[122] and eighteen in Brazil.[123]

What has the Church done to make amends with Black communities?

The Church has repeatedly denounced racism,[124] including specific condemnation of white supremacist attitudes and behavior.[125] In 2008 and 2018, it sponsored official celebrations of the revelation on the priesthood.[126]

Other programs organized by Black Saints with Church support have showcased faith, music, and culture,[127] and the Church has led major initiatives in African American genealogy.[128] The Church has also worked on humanitarian and education projects with diverse groups, including Black 14 Philanthropy[129] and the NAACP.[130]

- Matt

“My heart goes out to those who have been affected by this. God is mysterious, and has restricted priesthood power to the Levites and Jews in the past, so while it doesn’t disprove the validity of the church to me, it does instill a desire to be more aware of black struggles.”

about this topic

about this topic