Wesley Walters argues in the Westminster Theological Journal that Joseph Smith had a "trial" in 1826 based on evidence from bills.

- Type

- Periodical

- Source

- Wesley P. Walters CriticNon-LDS

- Hearsay

- Secondary

- Reference

Wesley P Walters, “Joseph Smith’s Bainbridge, N.Y., Court Trials,” Westminster Theological Journal 36, no. 2 (1973): 123–128 (Logos Bible edition)

- Scribe/Publisher

- Westminster Theological Journal, Logos

- People

- Joseph Chamberlain, Zechariah Tarble, James Humphrey, Miriam Stowell, Ebenezer Hatch, Addison Austin, Newel Knight, Rhoda Stowell, Joseph Smith, Jr., Fred Poffarl, Wesley P. Walters, John S. Reed, Abram W. Benton

- Audience

- Reading Public

- Transcription

The 1830 Trial

The Mormon Prophet recorded in his history that he was brought to trial in the town of Bainbridge, Chenango County, New York, in 1830 shortly after his organization of the church in April. Smith at that time was at the home of one of his converts, Newel Knight, when he was “visited by a constable, and arrested by him on a warrant, on the charge of being a disorderly person.” “On the day following,” Smith continues, “a court was convened for the purpose of investigating those charges,” at which investigation, he adds, there were “many witnesses called up against me.” One of the men employed to defend the young Prophet was John Reid, whose personal reminiscence also appears in a footnote in Joseph’s History. Mr. Reid recalls that they “had him arraigned before Joseph Chamberlain,” that “the case came on about 10 o’clock a.m.” and “the trial closed about 12 o’clock at night.”

There is now contemporary evidence to confirm Smith’s story of this trial in the form of the bills for their services submitted to the county by the constable and the judge at the trial. These bills were in the material Chenango County had in dead storage in the basement of the county jail in Norwich, New York, and were turned up in the summer of 1971 by Mr. Fred Poffarl of Philadelphia and the writer. They were bound together in a bundle with the other 1830 Bainbridge bills submitted to the County Board of Supervisors for approval and payment. They appeared still to have been tied with the same pink cord that was placed around them when the treasurer packaged them up for storage after they had been allowed, marked “passed,” and the total due each claimant carefully entered into the “Supervisor’s Journal” beside his name.

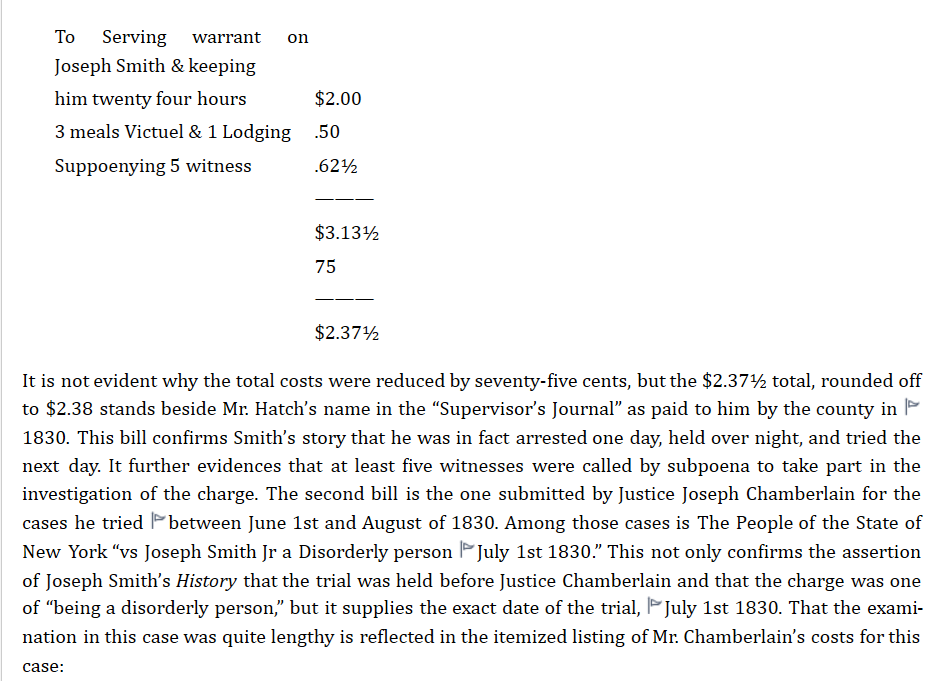

One of the bills was submitted by the constable, Ebenezer Hatch, “Dated at South Bainbridge July 4th, 1830,” and reads:

To Serving warrant on Joseph Smith & keeping

him twenty four hours

$2.00

3 meals Victuel & 1 Lodging

.50

Suppoenying 5 witness

.62½

———

$3.13½

75

———

$2.37½

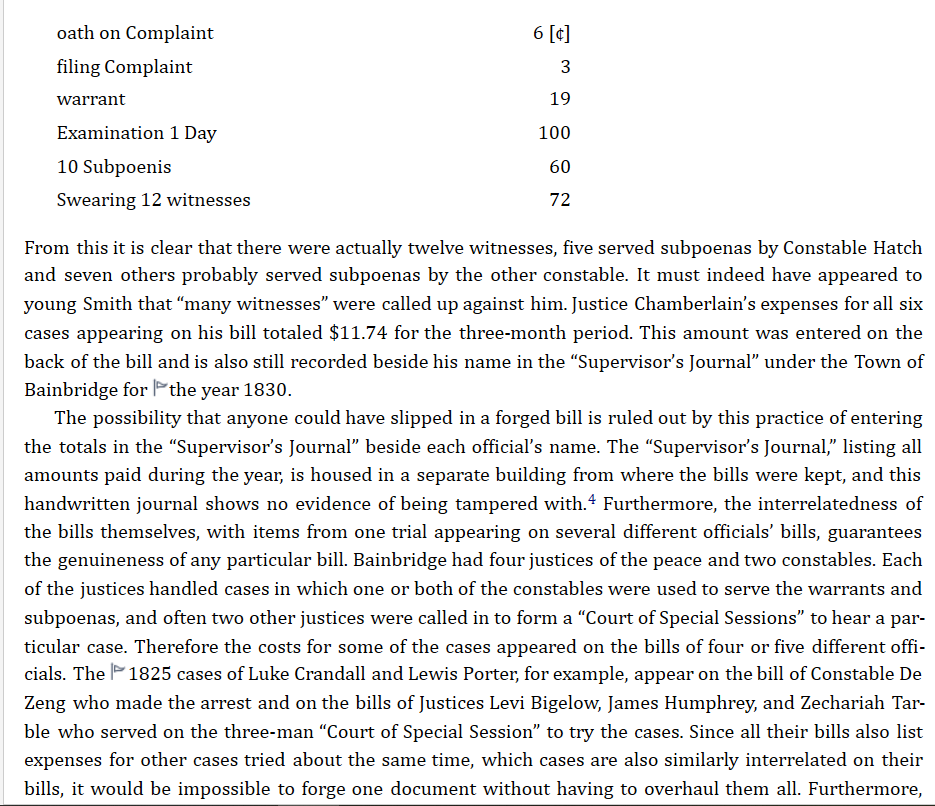

It is not evident why the total costs were reduced by seventy-five cents, but the $2.37½ total, rounded off to $2.38 stands beside Mr. Hatch’s name in the “Supervisor’s Journal” as paid to him by the county in 1830. This bill confirms Smith’s story that he was in fact arrested one day, held over night, and tried the next day. It further evidences that at least five witnesses were called by subpoena to take part in the investigation of the charge. The second bill is the one submitted by Justice Joseph Chamberlain for the cases he tried between June 1st and August of 1830. Among those cases is The People of the State of New York “vs Joseph Smith Jr a Disorderly person July 1st 1830.” This not only confirms the assertion of Joseph Smith’s History that the trial was held before Justice Chamberlain and that the charge was one of “being a disorderly person,” but it supplies the exact date of the trial, July 1st 1830. That the examination in this case was quite lengthy is reflected in the itemized listing of Mr. Chamberlain’s costs for this case:

oath on Complaint

6 [¢]

filing Complaint

3

warrant

19

Examination 1 Day

100

10 Subpoenis

60

Swearing 12 witnesses

72

From this it is clear that there were actually twelve witnesses, five served subpoenas by Constable Hatch and seven others probably served subpoenas by the other constable. It must indeed have appeared to young Smith that “many witnesses” were called up against him. Justice Chamberlain’s expenses for all six cases appearing on his bill totaled $11.74 for the three-month period. This amount was entered on the back of the bill and is also still recorded beside his name in the “Supervisor’s Journal” under the Town of Bainbridge for the year 1830.

The possibility that anyone could have slipped in a forged bill is ruled out by this practice of entering the totals in the “Supervisor’s Journal” beside each official’s name. The “Supervisor’s Journal,” listing all amounts paid during the year, is housed in a separate building from where the bills were kept, and this handwritten journal shows no evidence of being tampered with. Furthermore, the interrelatedness of the bills themselves, with items from one trial appearing on several different officials’ bills, guarantees the genuineness of any particular bill. Bainbridge had four justices of the peace and two constables. Each of the justices handled cases in which one or both of the constables were used to serve the warrants and subpoenas, and often two other justices were called in to form a “Court of Special Sessions” to hear a particular case. Therefore the costs for some of the cases appeared on the bills of four or five different officials. The 1825 cases of Luke Crandall and Lewis Porter, for example, appear on the bill of Constable De Zeng who made the arrest and on the bills of Justices Levi Bigelow, James Humphrey, and Zechariah Tarble who served on the three-man “Court of Special Session” to try the cases. Since all their bills also list expenses for other cases tried about the same time, which cases are also similarly interrelated on their bills, it would be impossible to forge one document without having to overhaul them all. Furthermore, since each of the bills is in the distinctive handwriting of the officials submitting the claim, and matches their handwriting on other bills handed in during other years they were in office, the possibility of forgery in such a complex system is entirely ruled out. Although the bills had lain unattended for a long period of time, and even though no one else was present in the jail basement when Mr. Poffarl and the writer made this unusual discovery, this interrelatedness is a virtual guarantee of the authenticity of these bills and we need not fear that some avid follower of Joseph Smith could have planted this evidence to give support to his story.

Joseph Smith’s History gives a portion of the testimony given by Josiah Stoal [Stowell]. This material could be verified as to accuracy if we could locate Justice Chamberlain’s Docket Book, but the location of this, if it is still extant, is unknown to members of his family. However, the earliest printed account of the trial, which appeared in the April 9, 1831, issue of the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate, does mention that testimony was given by Josiah Stowell, thus giving an added point of corroboration to Smith’s story. The writer of that article, dated at South Bainbridge March 1831, signs himself as “A.W.B.” From other articles in this periodical, the late Dale Morgan who first uncovered this account identifies the writer as A. W. Benton. It is most likely that this is the same Benton of whom Joseph Smith records a little later in his history that “a young man named Benton, of the same religious [Presbyterian] faith, swore out the first warrant against me.”9 The Mormon leader’s account also adds that Stowell’s two daughters, probably Rhoda and Miriam, were also called, while the Evangelical Magazine adds to the list of witnesses the names of Mr. Addison Austin and the two Mormon disciples Joseph Knight and his son Newel. Joseph Smith does not mention the Knights as participating in the South Bainbridge trial, but he does name them as participating in the Colesville trial that immediately followed it. It is quite likely that their testimony was given at both trials as a key part of his defense. Smith mentions that the matter of his money digging was brought up at the Colesville trial and the Benton article records that it also played a part in the Bainbridge trial.

In regard to this money digging, Benton informs us that an attempt was made to have Josiah Stowell admit that Smith had lied to him about his ability to locate buried treasures. Mr. Benton recalls the questioning of Stowell to have been as follows

Did Smith ever tell you there was money hid in a certain place which he mentioned? Yes. Did he tell you, you could find it by digging? Yes. Did you dig? Yes. Did you find any money? No. Did he not lie to you then and deceive you? No! the money was there, but we did not get quite to it! How do you know it was there? Smith said it was!

Benton also reports that Addison Austin testified that he had asked Smith at the time Stowell was doing his money digging “to tell him honestly whether he could see this money or not. Smith hesitated some time, but finally replied, ‘to be candid, between you and me, I cannot, any more than you or any body else; but any way to get a living.’ ” We have no way of checking Mr. Austin’s testimony as to Joseph Smith’s admitted inability to see buried treasure, but there can no longer be any doubt that prior to his printing and sale of the Book of Mormon he had gained part of his livelihood by “glass-looking” for hidden treasures. Joseph himself provides us with very little information on this period of his life, but more light on his glass-looking occupation in his pre-Mormon days is provided by a still earlier court trial at South Bainbridge for which striking corroboration in the form of the officials’ bills has also been discovered

- Citations in Mormonr Qnas

The B. H. Roberts Foundation is not owned by, operated by, or affiliated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.