First Presidency issues the "Political Manifesto" during the April 1896 General Conference: Church leaders must get permission from leadership before running for political office.

- Type

- News (traditional)

- Hearsay

- DirectReprint

- Reference

"To the Saints," The Deseret Weekly 52, no. 17 (April 11, 1896): 532-34

- Scribe/Publisher

- Deseret Weekly

- People

- Edward Stevenson, John Henry Smith, John W. Taylor, First Presidency, Francis M. Lyman, George Reynolds, Lorenzo Snow, Rulon S. Wells, Abraham H. Cannon, Brigham Young, Jr., Jonathan G. Kimball, Wilford Woodruff, Robert T. Burton, George Q. Cannon, Seymour B. Young, George Teasdale, Anthon H. Lund, Marriner W. Merrill, Joseph F. Smith, William B. Preston, Franklin D. Richards, Christian Daniel Fjeldsted, John R. Winder, B. H. Roberts, Heber J. Grant, John Smith

- Audience

- Reading Public, Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Transcription

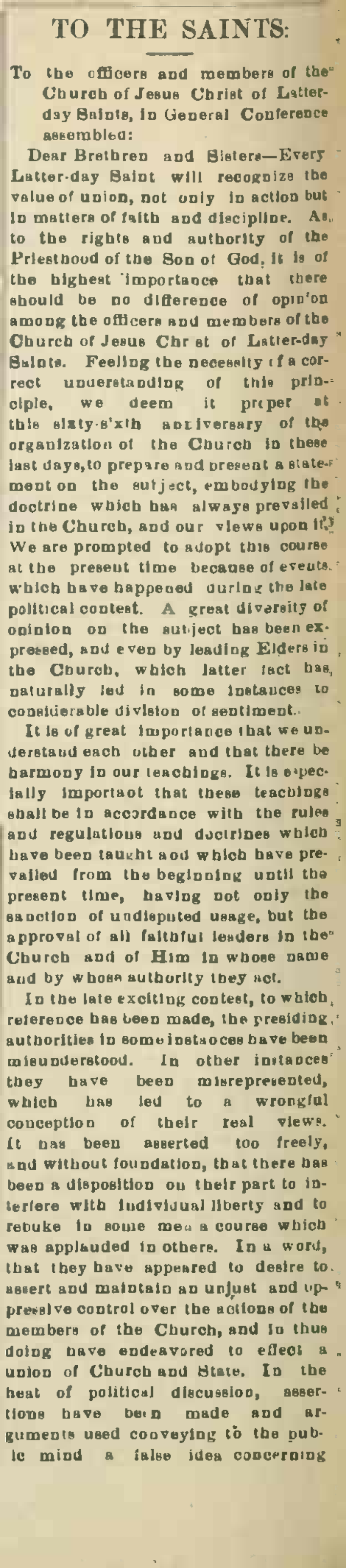

To the officers and memebrs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in General Conference assembled:

Dear Brethren and Sisters—Every Latter-day Saint will recognize the value of union, not only in action but in matters of faith and discipline. As to the rights and authority of the Priesthood of the Son of God, it is of the highest importance that there should be no difference of opinion among the officers and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Feeling the necessity of a correct understanding of this principle, we deem it proper at this sixty-sixth anniversary of the organization of the Church in these last days, to prepare and present a statement on the subject, embodying the doctrine which has always prevailed in the Church, and our views upon it. We are prompted to adopt this course at the present time because of events which have happened during the late political contest. A great diversity of opinion on the subject has been expressed, and even by leading Elders in the Church, which latter fact has naturally led in some instances to considerable division of sentiment.

It is of great importance that we understand each other and that there be harmony in our teachings. It is especially important that these teachings shall be in accordance with the rules and regulations and doctrines which have been taught and which have prevailed from the beginning until the present time, having not only the sanction of undisputed usage, but the approval of all faithful leaders in the Church and of Him in whose name and by whose authority they act.

In the late exciting contest, to which reference has been made, the presiding authorities to some instances have been misunderstood. In other instances they have been misrepresented, which has led to a wrongful conception of their real views. It has been asserted too freely, and without foundation, that there has been a disposition on their part to interfere with individual liberty and to rebuke in some men a course which was applauded in others. In a word, that they have appeared to desire to assert and maintain an unjust and oppressive control over the actions of the members of the Church, and in thus doing have endeavored to effect a union of Church and State. In the heat of political discussion, assertions have been made and arguments used conveying to the public mind a false idea concerning the position of the officers of the Church, and leaving the impression that there has been and was now being made an attempt to accomplish the union above referred to. Now that the excitement has passed, and calmer reason has resumed its sway, we think it prudent to set forth, so that all may understand, the exact position occupied by the leading authorities of the Church.

In the first place we wish to state in the most positive and emphatic language that at no time has there ever been any attempt or even desire on the part of the leading authorities referred to to have the Church in any manner encroach upon the rights of the State or to unite in any degree the functions of the one with those of the other.

Peculiar circumstances have surrounded the people of Utah. For many years a majority of them in every portion of the Territory belonged to one Church, every reputable member of which was entitled to hold and did hold some ecclesiastical office. It is easy to see how, to the casual observer, it might appear singular that so many officers of the Church were also officers of the State; but while this was in fact the case, the distinction between the Church and the State throughout those years was carefully maintained. The President of the Church held for eight years the highest civil office in the community, having been appointed by the national administration governor of the Territory. The first secretary of the Territory was a prominent Church official. An Apostle represented the Territory in Congress as a delegate during ten years. The members of the Legislature held also offices in the Church. This was unavoidable; for the most suitable men were elected by the votes of the people, and, as we have stated, every reputable man in the entire community held some Church position, the most energetic and capable holding leading positions. This is all natural and plain enough to those who consider the circumstances; but it furnished opportunity for those who were disposed to assail the people of the Territory to charge them with attempting to unite Church and State. A fair investigation of the conditions will abundantly disprove the charge and show its utter falsity.

On behalf of the Church of which we are leading officers, we desire again to state to the members and also to the public generally, that there has not been, or is there, the remotest desire on our part or on the part of our co-religionists to do anything looking to a union of Church and State.

We declare that there has never been any attempt to curtail individual liberty-the personal liberty of any of the officers or members of the Church. The First Presidency and other leading officers did make certain suggestions to the people when the division on party lines took place. That movement was an entirely new departure, and it was necessary, in order that the full benefit should not be lost which was hoped to result from this new political division, that people who were inexperienced should be warned against hasty and ill-considered action. In some cases they were counseled to be wise and prudent in the political steps they were about to take, and this with no idea of winning them against their will to either side. To this extent, and no further, was anything said or done upon this question, and at no time and under no circumstances was any attempt made to say to voters how they should cast their ballots. Any charge that has been made to the contrary is utterly false.

Concerning officers of the Church themselves, the feeling was generally expressed in the beginning of the political division spoken of that it would be prudent for leading men not to accept of office at the hands of the political party to which they might belong. This counsel was given to men of both parties alike-not because it was thought that there was any impropriety in religious men holding civil office, not to deprive them of any of the rights of citizenship, but because of the feeling that it would be better under all the circumstances which had now arisen to avoid any action that would be likely to create jealousy and ill-feeling. An era of peace and good-will seemed to be dawning upon the people, and it was deemed good to shun everything that could have the least tendency to prevent the consummation of this happy prospect. In many instances, however, the pressure brought to bear upon efficient and popular men by the members of the parties to which they belonged was of such a character that they had to yield to the solicitation to accept nomination to office, or subject themselves to the suspicion of bad faith in their party affiliations. In some cases they did this without consulting the authorities of the Church; but where important positions were held, and where the duties were of a responsible and exacting character, some did seek the counsel and advice of the leading Church authorities before accepting the political honors tendered them. Because some others did not seek this counsel and advice, ill-feeling was engendered, and undue and painful sensitiveness was stimulated; misunderstanding readily followed, and as a result the authorities of the Church were accused of bad faith and made the subjects of bitter reproach. We have maintained that in the case of men who hold high positions in the Church, whose duties are well defined, and whose ecclesiastical labors are understood to be continuous and necessary, it would be an improper thing to accept political office or enter into any vocation that would distract or remove them from the religious duties resting upon them, without first consulting and obtaining the approval of their associates and those who preside over them. It has been understood from the very beginning of the Church that no officer whose duties are of the character referred to, has the right to engage in any pursuit, political or otherwise, that will divide his time and remove his attention from the calling already accepted. It has been the constant practice with officers of the Church to consult or, to use our language, to "counsel" with their brethren concerning all questions of this kind. They have not felt that they were sacrificing their manhood in doing so, nor that they were submitting to improper dictation, nor that in soliciting and acting upon the advice of those over them, they were in any manner doing away with their individual rights and agency, nor that to any improper degree were their rights and duties as American citizens being abridged or interfered with. They realized that in accepting ecclesiastical office they assumed certain obligations; that among these was the obligation to magnify the office which they held, to attend to its duties in preference to every other labor, and to devote themselves exclusively to it with all the zeal, industry and strength they possessed, unless released in part or for a time by those who preside over them. Our view, and it has been the view of all our predecessors, is that no officer of our Church, especially those in high standing, should take a course to violate this long-established practice. Rather than disobey it, and declare himself by his actions defiantly independent of his associates and his file leaders, it has always been held that it would be better for a man to resign the duties of his Priesthood: and we entertain the same view today.

In view of all the occurrences to which reference has been made, and to the diversity of views that have arisen among the people in consequence, we feel it to be our duty to clearly define our position, so there may be no cause hereafter for dispute or controversy upon the subject:

First-We unanimously agree to and promulgate as a rule that should always be observed in the Church and by every leading official thereof, that before accepting any position, political or otherwise, which would interfere with the proper and complete discharge of his ecclesiastical duties, and before accepting a nomination or entering into engagements to perform new duties, said official should apply to the proper authorities and learn from them whether he can, consistently with the obligations already entered into with the Church upon assuming his office, take upon himself the added duties and labors and responsibilities of the new position. To maintain proper discipline and order in the Church, we deem this absolutely necessary; and in asserting this rule, we do not consider that we are infringing in the least degree upon the individual rights of the citizen. Our position is that a man having accepted the honors and obligations of ecclesiastical office in the Church cannot properly of his own volition make those honors subordinate to or even coordinate with new ones of an entirely different character; we hold that unless he is willing to counsel with and obtain the consent of his fellow-laborers and presiding officers in the Priesthood, he should be released from all obligations associated with the latter, before accepting any new position.

Second-We declare that in making these requirements of ourselves and our brethren in the ministry, we do not in the least desire to dictate to them concerning their duties as American citizens, or to interfere with the affairs of the State; neither do we consider that in the remotest degree we are seeking the union of Church and State. We once more here repudiate the insinuation that there is or ever has been an attempt by our leading men to trespass upon the ground occupied by the State, or that there has been or is the wish to curtail in any manner any of its functions.

Your brethren,

WILFORD WOODRUFF,

GEO. Q. CANNON,

JOS. F. SMTIH,

First Presidency

LORENZO SNOW,

F. D. RICHARDS,

BRIGHAM YOUNG,

FRANCIS M. LYMAN,

JOHN HENRY SMITH,

GEORGE TEASDALE,

HEBER J. GRANT,

JOHN W. TAYLOR,

MARRINER W. MERRILL,

ABRAHAM H. CANNON,

Apostles

JOHN SMITH,

Patriarch,

SEYMOUR B. YOUNG,

C. D. FJELDSTED,

B. H. ROBERTS

GEORGE REYNOLDS,

JONATHAN G. KIMBALL,

RULON S. WELLS,

EDWARD STEVENSON,

First Council of Seventies.

Wm. B. PRESTON,

R. T. BURTON,

JOHN R. WINDER,

Presiding Bishopric.

SALT LAKE CITY, April 6th, 1896.

Note—The reason the signature of Apostle Anton H. Lund does not appear in connection with those of his quorum is because he is absent, presiding over the European mission. He, however, will be given the opportunity of appending his signature when he returns home.

- Citations in Mormonr Qnas

The B. H. Roberts Foundation is not owned by, operated by, or affiliated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.