Some movies aren't Mormon, but are still Mormon by adoption—like Napoleon Dynamite or The Princess Bride. Pixar’s Soul is one of those movies.

In this movie, Joe Gardner isn’t struggling to find happiness; he’s completely consumed by his pursuit of it. As a jazz musician who believes his life will only have meaning once he lands his big break, Joe falls into a familiar trap—one that many Latter-day Saints might recognize: mistaking a single moment for the whole picture.

There are plenty of other overlaps between Latter-day Saint theology and the movie Soul. From the Great Before and the pre-mortal existence to the Great Beyond and eternal progression, Soul echoes these gospel principles that have been taught by prophets and apostles for centuries.

The Great Before and Eternal Identity

Let's start at the beginning—not of the movie, but of each soul.

In Soul, unborn spirits prepare for their life on earth in the whimsical realms of the Great Before—also called the You Seminar. This world looks like a dreamy, pastel-colored wonderland—soft blues, purples, and pinks blending into a vast, floating space. There, the souls build their personalities and traits that will continue to be a part of them on earth.

In an NPR article, Pete Docter, a co-writer and co-director of the film, said he spoke to many "priests and rabbis and experts" to research different beliefs on the soul, the afterlife, and the spiritual world. He added:

"What we found was that most of them have a lot to say about what happens after we die — but very few talk about what happened before. So that meant we were kind of free to make stuff up, which is my favorite place to be."

But this Great Before does resonate with Latter-day Saints. Just like the souls attending the You Seminar, members of the Church believe we developed our identities and our spiritual capabilities in the pre-existence, or life before earth.

In Jeremiah 1:5, the Lord tells the prophet, "Before I formed thee in the belly, I knew thee." Abraham 3:22 expands on this, describing "the intelligences that were organized before the world was."

The movie also imagines souls being guided by mentors to find their "spark," similar to the idea that we lived with Heavenly Parents, preparing for Earth life and being blessed with unique spiritual gifts.

The details may differ, but the core doctrinal idea remains: we existed before birth, and that existence helps define our earthly and eternal identity.

The Agency of Jazz and Life on Earth

One of the most compelling themes in Soul is how jazz itself becomes a metaphor for life. Jazz music is varied, rhythmic, and emotional and values improvisation—the freedom to take the music anywhere the musician wants. As the Smithsonian's post on jazz describes:

Jazz is about making something familiar—a familiar song—into something fresh. And about making something shared—a tune that everyone knows—into something personal.

In Soul, the music shows both how the unexpected situations of life force us to adapt and how, even though life might follow the same base structure, our paths are deeply personal.

That idea closely parallels Latter-day Saint teachings on agency and progression. We each have a divine nature, spiritual gifts, and an eternal identity—our fundamental "notes"—but how we express them is up to us.

Agency—the ability to make choices—is a foundational principle in the restored gospel. Soul reflects this idea as its characters navigate life’s possibilities, echoing 2 Nephi 2:27: "Wherefore, men are free according to the flesh . . . they are free to choose liberty and eternal life . . . or to choose captivity and death."

But to do so, in both Soul and Latter-day Saint doctrine, we need a body on earth. The movie emphasizes how a physical body is capable of experiences beyond the experiences that of a spirit. Through the character 22’s journey while in Joe's body—tasting pizza, feeling autumn leaves, and experiencing simple joys—Soul unintentionally illustrates a belief found in Doctrine and Covenants 93:33: "Spirit and element, inseparably connected, receive a fulness of joy."

This is further implied by the way people’s post-mortal spirits appear to be changed by the mortal lives they live. To put this in a more Latter-day Saint phrasing, Soul presents humans as spiritual beings having a mortal experience that they take with them after death.

The Great Beyond and Eternal Progression

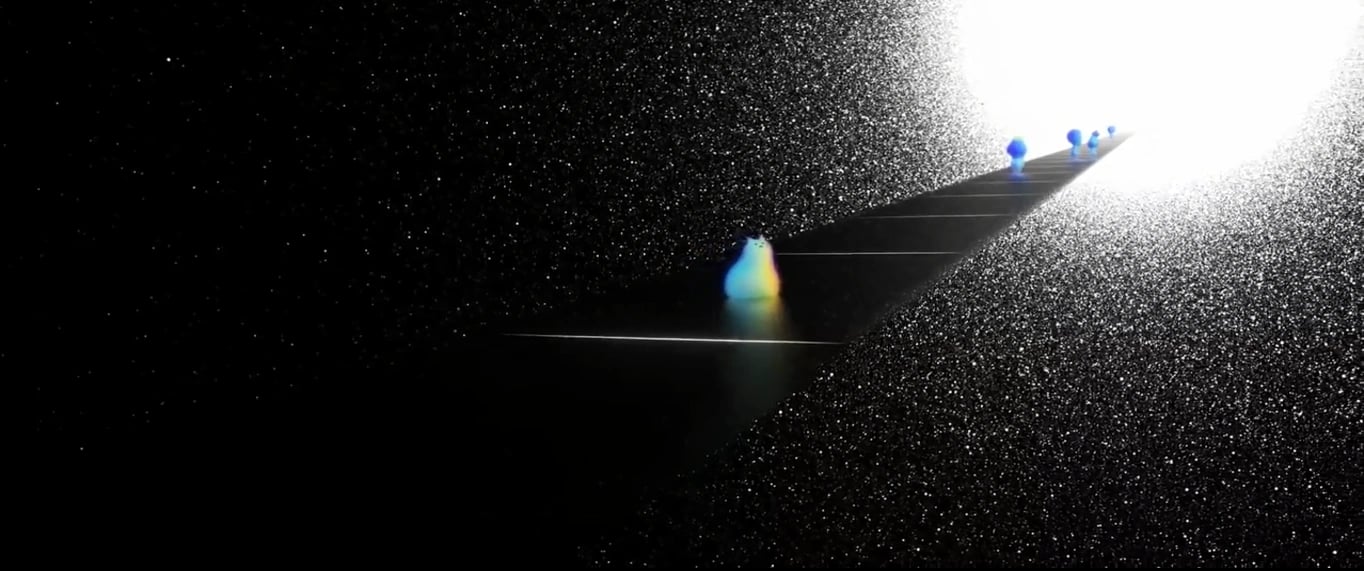

Of all the scenes in Soul, its depiction of the afterlife differs most from Latter-day Saint beliefs. The film presents the "Great Beyond" as a glowing destination reached by a conveyor belt, which doesn't tell us much about what comes after.

But maybe Joe's split-second decision to jump off the conveyor belt and try to get back to his body tells us enough to match it with one part of Latter-day Saint doctrine—the ability to make choices even after death.

This may already be hinted at in Soul, with some of the mentors for pre-mortal spirits including people who had already lived like Shakespeare or Carl Jung, but Latter-day Saint beliefs take it much further. Doctrine and Covenants 138:30 describes it as a place where the gospel continues to be preached, allowing for personal growth and agency even after this life.

The Regular Old Greater Purpose

And while the similarities between Soul and Latter-day Saint teachings are coincidental, they tap into doctrinal ideas of the premortal life, agency, and progression. It can be fun to explore these ideas through the film.

With that in mind, here is a last connection for you:

By the end of Soul, Joe comes to a realization that feels deeply familiar to Latter-day Saint theology: life’s purpose isn’t about reaching one grand achievement—it’s about embracing the full experience.

We sometimes think of life in terms of big milestones—graduations, jobs, marriage, children, promotions. But Soul reminds us that meaning isn’t found only in these big moments. It’s in the little things too—the jazz solo and the pizza slice, the temple worship and the TV show, the ministering visit and the morning commute.

We believe in eternal progression, in reaching our divine potential. But we also believe in a God who gave us taste buds and laughter, music and sunsets. A God who delights in our learning and our joy. Like Joe Gardner, we’re here to experience it all—not just to prepare for some future glory, but to recognize the glory in every note we play.

Maybe that’s what Lehi meant when he said:

"Men are, that they might have joy" (2 Nephi 2:25).