The Bible you have on your shelf right now has gone through quite the journey to get to where it is today—from a group of seventy scholars in ancient Egypt to Martin Luther, centuries later. It's no wonder the eighth article of faith specifically mentions believing "the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly."

Nephi's Preview

The prophet Nephi got a sneak preview of the whole process too. In a vision with an angel recorded in 1 Nephi 13, Nephi wrote he "beheld a book, and it was carried forth among [the Gentiles]." The angel explained that this book, the Bible "proceeded forth from the mouth of a Jew; and when it proceeded forth from the mouth of a Jew it contained the fulness of the gospel of the Lord, of whom the twelve apostles bear record; and they bear record according to the truth which is in the Lamb of God."

But then his angelic guide explained that some of those precious truths would be lost along the way (1 Nephi 13:24-26). So what exactly happened?

The Septuagint: Where Greek Meets Hebrew

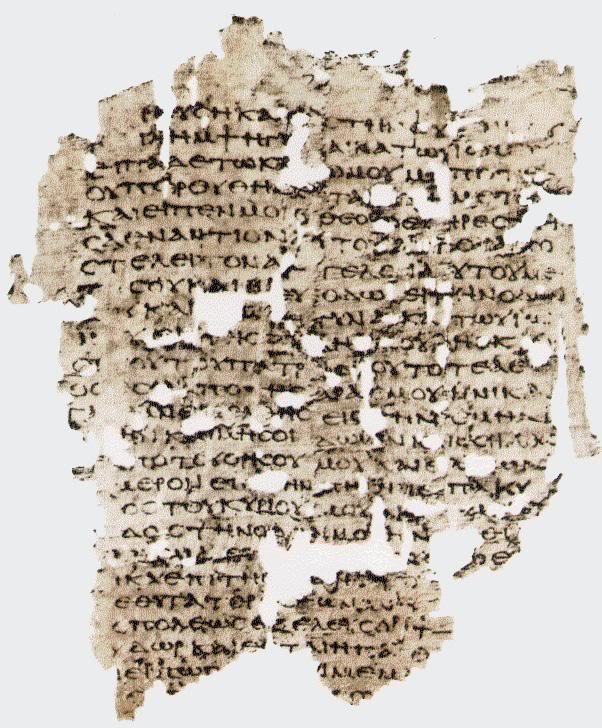

Think of the Septuagint as the Bible's first major translation project. It's the earliest compilation of biblical texts known today and is a Greek translation of the Old Testament.

According to tradition, the king of Egypt in the second or first century BC commissioned 70 scholars—hence the name—to translate the Hebrew scriptures into Greek. These scholars included not only what we now call the Old Testament but also some bonus content we now know as the Apocrypha (Tobit, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees, etc.).

When quoting the Old Testament, the apostles in the New Testament seemed to use the Septuagint. This is also true for early Christian writers—many of whom knew Greek but didn't know Hebrew.

The New Testament: Early Christian Mixes

After Jesus's resurrection, many of His disciples started writing down their experiences. Others, like Paul, wrote letters to Christian communities to encourage them in their new faith and give them directions. These writings were circulated by believers and began to be used alongside the Old Testament. But here's where it gets interesting: how did early Christians decide which writings would make the cut?

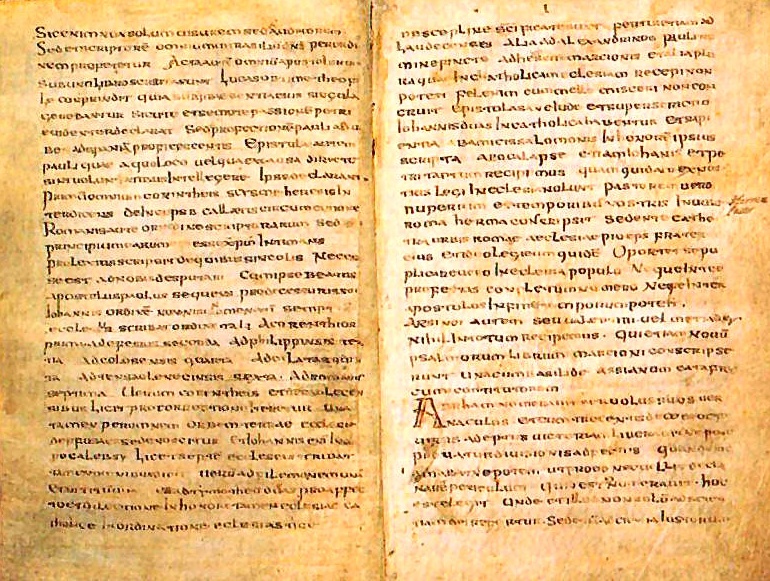

Enter the Muratorian Canon.

This second-century AD text gives us the earliest list of texts that were approved as scripture by a group of Christians. It included most of what is now in the New Testament except for Hebrews, James, 1 & 2 Peter, and Jude. It also had some non-canonical books like Apocalypse of Peter and Wisdom of Solomon.

Other early Christian writers followed this example and compiled more lists of which books congregations used and approved of. For example, Eusebius of Caesarea's Ecclesiastical History from the early fourth century AD does so in Book III, Chapter 25 and Book VI, Chapter 25.

But perhaps more significant to the process of canonizing the New Testament was Athanasius of Alexandria's Easter letter of 367 AD, which listed the books of the New Testament as those approved by the church at that time. In the early fifth century, a church council in Carthage, Africa, ratified the same list of books found in Athanasius' Easter list—the earliest example of a church-wide decision on what was and was not scripture.

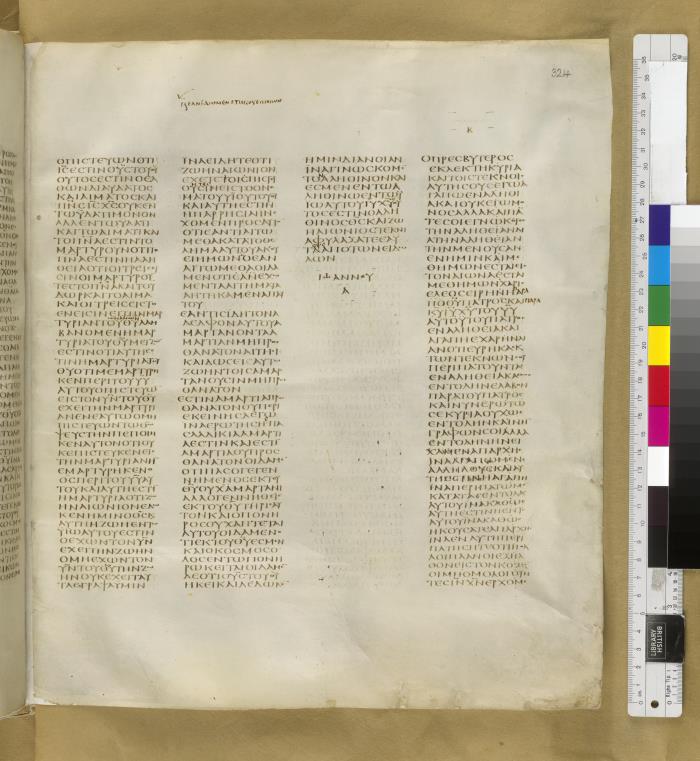

Codex Sinaiticus: The Fourth-Century Game Changer

Around the same time as Athanasius's letter, something big happened: the creation of Codex Sinaiticus.

The Codex Sinaiticus is one of the earliest known manuscripts to contain the texts of the Bible. Likely written sometime during the mid-fourth century AD, it contains the Old Testament, Apocrypha, New Testament, the Epistle of Barnabas, and the Shepherd of Hermas. The last two are now generally classified with the writings of the Apostolic Fathers, who were leaders of Christian communities after the apostles.

Between the lists and this codex, a regular group of scriptural books was beginning to form by the fourth century.

Martin Luther: The Protestant Movement

Let's fast forward to the 1500s. Up until this point, the Bible stayed essentially unchanged in Western Christianity—until Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation.

After leaving the Catholic Church, Martin Luther translated the Bible into German and—controversially—moved some things around. Luther used a recent compilation of New Testament manuscripts made by the humanist scholar Erasmus to create his translation. He had been questioning the authority of some of the Old Testament books while translating because there were no known Hebrew texts of them. So, Martin Luther moved these books into a special section between the Old and New Testaments, and it became known as the Apocrypha.

It was still common to include the Apocrypha in the Bible in future Protestant translations (including in the Bible Joseph Smith used with the Joseph Smith translation). But by the late nineteenth century, more and more publishers were leaving it out of their Bibles entirely.

KJV to Today

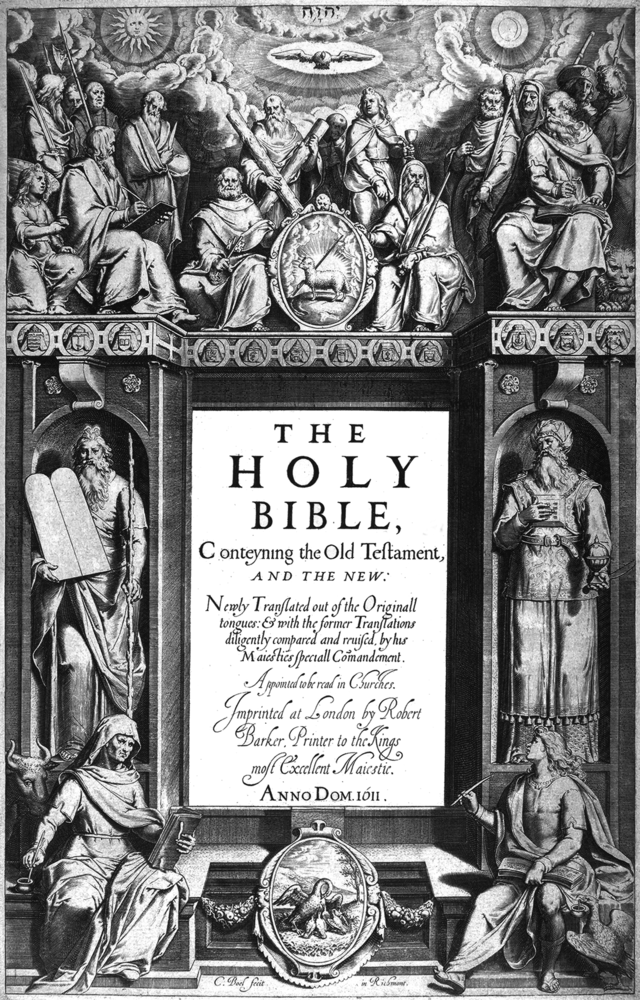

The Bible continued to evolve in use and translation over the years that followed, but the seventeenth century would bring the version most important to Latter-day Saints.

In 1604, King James commissioned a Bible translation that is now called the Authorized Version or the King James Version (not named after anyone in particular). He assembled a team of about 50 scholars to evaluate it in committees at Oxford, Cambridge, and Westminster. It was intended to unify English-speaking Protestants and drew from Greek and Hebrew manuscripts, earlier English translations like the Geneva and Bishops' Bibles, and occasionally the Latin Vulgate.

Today, the Church uses a Latter-day Saint edition of the King James version for English-speaking members as part of the standard works. In August 1992, the First Presidency released a statement preferencing this version over others and encouraging "all members to have their own copies of the complete standard works and to use them prayerfully in regular personal and family study, and in Church meetings and assignments."

In more recent times, the Church Handbook directs that members should use Church-published or approved editions in their respective languages while in Church, but that "other editions of the Bible may be useful for private or academic study."