The Mountain Meadows Massacre

What is the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

On September 7, 1857, John D. Lee[BIO] led a group of Paiute Indians[BIO] and Mormon militiamen to attack the Baker-Fancher wagon train.[BIO][1] After a prolonged gun battle, siege, and feigned ceasefire agreement,[2] approximately 50 to 60 Mormon militiamen and a number of Paiute Indians arrived and massacred the wagon company on September 11, 1857.[3]

The attackers spared 17 children, all of whom were under the age of six,[4] who were taken in by local Latter-day Saint families before eventually returning to Arkansas.[5]

Timetable of key events relating to Mountain Meadows Massacre.

1846–1869

The Saints leave eastern U.S. territory and gather in Utah and surrounding areas.[7]

1850-1857

The Saints experience various conflicts with the federal government over the management of Utah territory.[8]

May 1857

June 1857

July 24, 1857

August 2, 1857

Brigham Young meets with Church leaders to discuss strategies related to the federal troops' impending attack on Utah, including gathering scattered Latter-day Saint settlements in the territory and calling missionaries abroad to come home.[13]

August 3, 1857

August 9, 1857

August 25, 1857

Smith camps near the Baker-Francher party, also known as the "Arkansas Company," on his way back to Salt Lake City, and the party is rumored to have given a "poisoned" ox to the local Native Americans.[17]

ca. September 3, 1857

ca. September 3, 1857

ca. September 3, 1857

September 4, 1857

Haight meets with John D. Lee and plans to arm Native Americans to attack the Arkansas wagon train, "give them a brush," and steal their cattle.[22]

September 5, 1857

September 6, 1857

The Attack, Siege, and Massacre at Mountain Meadows

September 7, 1857

Lee and the Paiutes make an initial attack on the wagon train, with casualties on both sides. The company circles its wagons and digs in to make a make-shift fort and a siege begins.[26]

September 7, 1857

September 7, 1857

September 7 or 8, 1857

September 8, 1857

On their way to the meadows, a group of men from Cedar City, including Higbee and Klingensmith, kill two emigrants who were on their way to Cedar City seeking help.[30]

September 9, 1857

Lee sends a courier to Haight in Cedar City and suggests that men be sent to protect the emigrants from the Indians so the conflict can be called off.[31]

September 9, 1857

Higbee arrives at the meadows and talks with Lee. They decide they need the militia to end the standoff, so Higbee returns to Cedar City to inform Haight.[32]

September 9, 1857

Haight meets with Dame and they decide that the members of the wagon train need to be killed to cover up the involvement of the Mormons in the violence.[33]

September 10, 1857

September 10, 1857

In council with Lee, Higbee and Pauite leaders decided to create a "decoy" and pretend to make a truce with the emigrants to draw them out of their wagon circle and kill them all except the "small children."[35]

September 10, 1857

James Haslam arrives in Salt Lake City to see Brigham Young on behalf of Haight. Brigham gives Haslam a letter instructing Haight to "not interfere" or "meddle" with the emigrants, and further tells Haslam to relay to Haight to let them "be protected and guarded out of the territory."[36] The correspondence arrives after the massacre.[37]

September 11, 1857

September 14, 1857

Unaware of the massacre three days previous, Brigham Young writes to Dame, directing him to prepare for the U.S. Government to arrive in force but to let others pass through the territory peacefully.[41]

November 20, 1857

Lee reports the massacre to Brigham Young, saying the Indians were responsible for it.[42]

Aftermath

1859

March 1859

July 5, 1859

Brigham Young records in his office journal that he wanted to bring charges against those responsible for the massacre if there was a fair trial without interference from the U.S. Army.[47]

1861-1865

The American Civil War interrupts further investigation into the massacre.[48]

July 1875

1874-1876

March 23, 1877

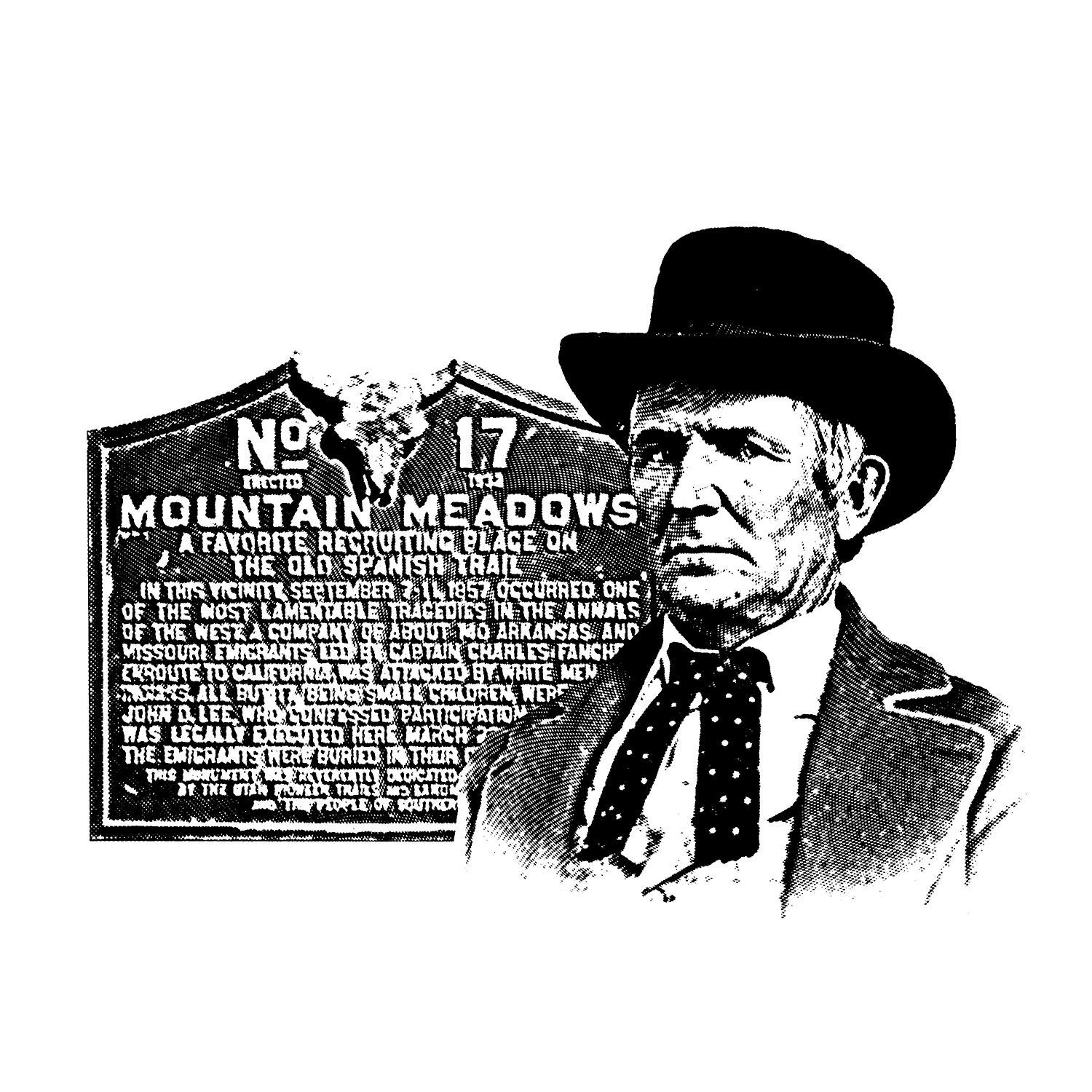

John D. Lee is executed by firing squad.[54]

March 31, 1877

Seventy-three years pass.

1950

April-May 1961

Forty-six years pass.

September 11, 1999

September 2007

Church leadership addresses the massacre on its 150th anniversary, condemning it.[60]

What motivated the Mormons to attack the Baker-Fancher wagon train in the first place?

In response to threats and harassment from the wagon train as it passed through Cedar City, Isaac Haight, the mayor of Cedar City, directed John D. Lee to convince the Pauites to attack and harass the emigrant train.[62]

Then what happened? How did the attack become a massacre?

After the initial attacks on the wagon company by the Paiute Indians under the direction of John D. Lee, the battle became a siege.[63] On the fifth day of the siege, the Iron County militia arrived and negotiated a surrender from the wagon train, which had run low on water and ammunition and needed to tend to their wounded.[64] The negotiated surrender was a ruse, however, and once the emigrants had been disarmed, the militia and Paiutes murdered them all except the youngest children.[65]

Why is it called the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

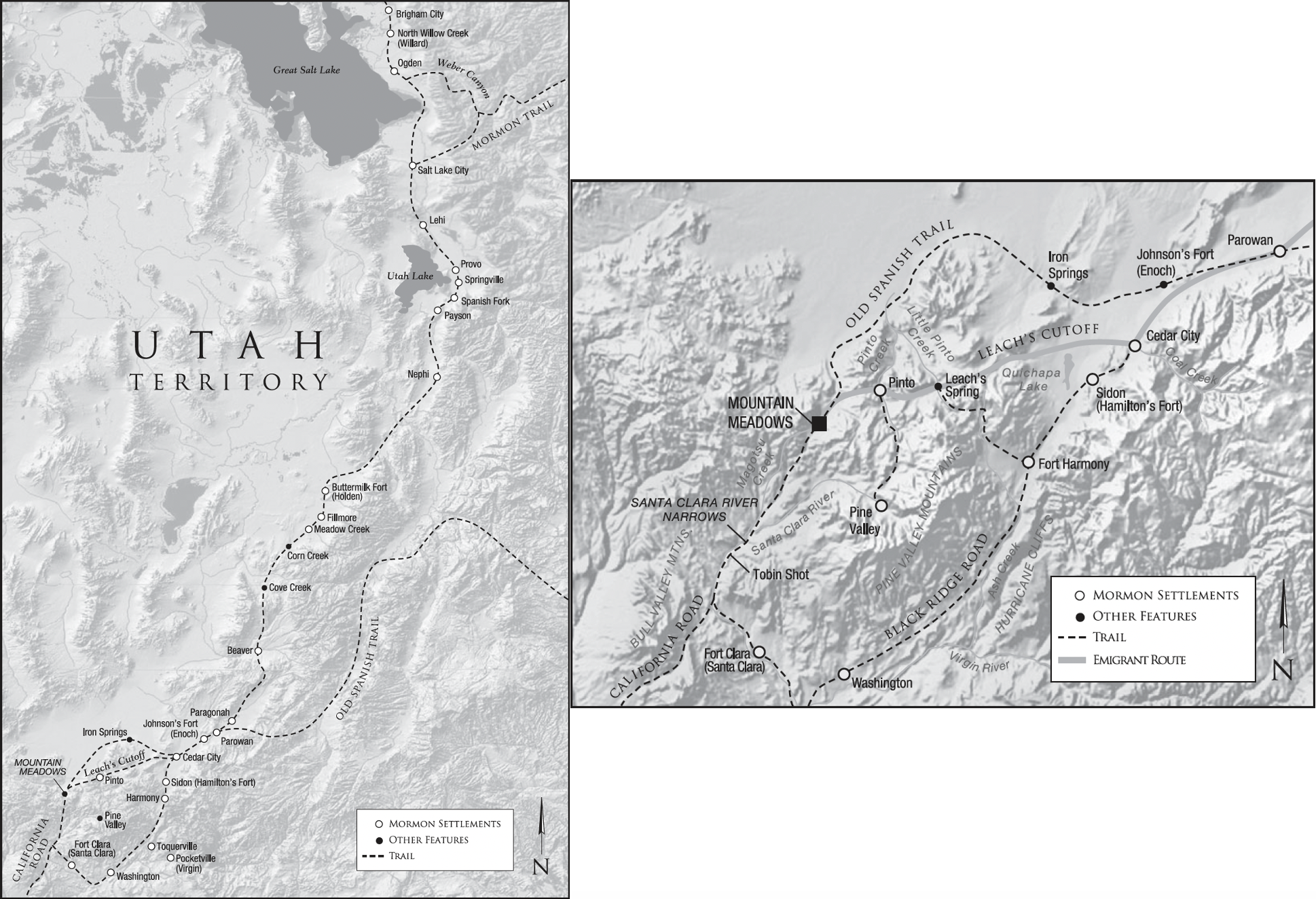

The attack and massacre took place at the site of Mountain Meadows, which is roughly 35 miles southwest of Cedar City, Utah.[66]

Why did it become a massacre?

There were likely several factors (see table below). One reason given at John D. Lee's second trial was that the massacre was carried out to hide the fact that Mormon settlers were involved in attacking the emigrants.[67][68]

Factors that Contributed to the Massacre

Contributing Factors | Commentary |

Political and Military | U.S. Army troops were marching toward Utah,[69] which would be later known as the "Utah War."[70]This would lead to violent rhetoric from Church leaders during this time (1857–1858)[71]as well as generate tension between members of the Church and the United States government.[72] |

The Cedar City Council decided that the emigrants knew that the Mormons had been involved in the initial attack on the wagon company and that if they made it to California, there would be grave consequences for the Mormon settlers.[73] | |

Social | There were rumors that some in the Baker-Fancher company had been in the mob that killed Joseph and Hyrum Smith and that they were boasting about it.[74] |

According to some reports, the emigrant company had given poisoned meat to Indians, leading to Native American deaths.[75] | |

Prior to the massacre, there were reported altercations between the emigrants and Paiutes.[76] | |

Religious | There were rumors that some in the Baker-Fancher company had been involved in the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, and this may have pushed some to keep covenants they had made to avenge the martyrdom.[77] |

During this time, Church leaders were delivering sermons that contained "blood atonement" rhetoric, often using graphic language and concepts such as the enemies of the Church and apostates being killed to atone for their sins.[78] |

Were any of these reasons enough to justify the massacre?

No.

So who was ultimately responsible for the massacre?

The evidence indicates that responsibility for the massacre rests primarily on members and leaders of the Iron County Militia, including William H. Dame, Isaac Haight, John Higbee, and John D. Lee (see table below).[79]

Key figures involved in the Mountain Meadows Massacre and related events (July–September 1857)

Role | Figure(s) | Commentary |

Key Figures | William H. Dame, Colonel, Bishop | William H. Dame was a colonel in the Iron County Militia. He initially directed the emigrants to be left alone, but Isaac Haight and John Higbee convinced him to murder all the adults in the Baker-Fancher Party to cover up Lee's involvement in the initial attack. Dame was indicted for his role in the massacre.[80] |

Isaac C. Haight, Mayor, Stake President, Major | Isaac C. Haight was the mayor of Cedar City, a Stake President, and a major in the Iron County Militia. He planned the initial attack by the Paiutes on the Baker-Fancher Party and then plotted the massacre. Haight was indicted for his role in the massacre.[81] | |

John M. Higbee, Major | John M. Higbee was a major in the Iron County Militia and a participant in the massacre of the Baker-Fancher Party. He was indicted for his role in the massacre.[82] | |

John D. Lee, Major | John D. Lee was a major in the Iron County Militia. He led the Pauites on the initial attack and siege and managed the faux surrender of the Baker-Fancher Party.[83] Lee was indicted and convicted for his role in the massacre and executed on March 23, 1877.[84] | |

Nephi Johnson[BIO] | Nephi Johnson was a second lieutenant in the Iron County Militia, a Paiute interpreter, and a participant in the attack on the Baker-Fancher Party.[85] | |

Philip Klingensmith | Philip Klingensmith was a private in the Iron County Militia and a participant in the massacre of the Baker-Fancher Party. He was indicted for his role in the massacre and turned state's evidence to avoid prosecution.[86] | |

(Southern) Paiute Indians[BIO] | This Native American tribe is localized in northern Arizona, southern Nevada, and southwestern Utah. Members of the tribe attacked and sieged the Baker-Fancher Party with John D. Lee and then assisted the Iron County Militia in the massacre.[87] | |

Iron County Militia[BIO] | Iron County Militia was also known variously as the Iron Military District of Utah Territory’s Nauvoo Legion or the Cedar City Militia. It was a local militia in Southern Utah composed entirely of Latter-day Saints and was the military unit that perpetrated the massacre.[88] | |

Missouri "Wildcats"[BIO] | The Missouri Wildcats was a group of Missourians reportedly traveling with the Baker-Fancher Party who reportedly made threats against Native Americans and Latter-day Saints.[89] | |

Baker-Fancher Party[BIO] | This party was an emigrant train of about 120–150 members traveling from Arkansas to California.[90] They reportedly harassed and threatened the Mormon settlers[91] and were the victims of the massacre. | |

Church Leadership | Jacob Hamblin[BIO] | Jacob Hamblin was a missionary and Indian interpreter. He housed the surviving children of the Baker-Fancher Party immediately after the massacre.[92] |

George A. Smith | George A. Smith, an apostle, told settlers in Southern Utah to store grain in anticipation of the looming arrival of federal troops.[93] | |

Daniel H. Wells[BIO] | Daniel H. Wells was the lieutenant general of the Nauvoo Legion and the second counselor to Brigham Young in the First Presidency. He led Latter-day Saint forces against federal troops in the Utah War.[94] | |

Brigham Young | Brigham Young was the President of the Church and the governor of Utah Territory.[95] | |

Federal | United States Federal Troops | United States President James Buchanan dispatched a military expedition of about 2,500 men to put down a supposed "Mormon rebellion" and install a new governor in Utah Territory.[96] |

Was Brigham Young responsible for the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

No. The evidence indicates that when he learned of the situation in Southern Utah, he instructed Isaac C. Haight to let the emigrants pass without interference.[97]

There is no known evidence suggesting that Brigham was involved in the massacre, but there were accusations made against him by John D. Lee's defense attorney and the popular press.[98]

But didn't John D. Lee accuse Brigham of orchestrating the massacre?

No. While Lee was bitter towards Brigham because he felt betrayed by him,[99] he said that Brigham knew nothing about the massacre, and if he did, he would have prevented it.[100]

Was John D. Lee responsible for the massacre?

Yes, in part. Though Lee was the only man legally held responsible for the massacre,[101] Isaac C. Haight and others also ordered or participated in the event.[102]

Were Native Americans also responsible for the massacre?

Yes, in part. Most sources agree they were willing participants in the massacre, though the massacre was organized and led by the local Mormon leadership of John D. Lee and Isaac Haight.[103]

As of September 2007, the official Paiute position is that the Native Americans had little, if any, involvement in the massacre.[104] This is also the claim made in Paiute oral traditions.[105]

Related Question

Did Latter-day Saints ever ally themselves with Indigenous groups against other white Americans?

Read more in Native American Extermination Order

Were the people who committed the massacre organized in some way?

Yes. The initial attack was directed by Isaac C. Haight, the mayor and stake president of Cedar City, and the subsequent massacre was organized and carried out by a branch of the territorial militia along with the Paiute Indians whom they had recruited.[106]

Did anyone in the local leadership oppose the idea of an attack?

Yes. Some people in Haight's council and other local leaders requested that he call off the attack and instead send an express rider to Brigham Young for guidance.[107]

Did the Baker-Fancher company actually poison the local animals and water?

Possibly, but probably not. There were multiple reports given at the time that the animals had been poisoned and the poisoning resulted in the death of some Native Americans.[108] However, these claims have never been verified, and recent studies have favored the theory that local animals died of anthrax rather than poisoning.[109]

What did Brigham Young know about the Baker-Fancher Company and when did he know about it?

On September 10, 1857, Brigham was told in a letter that Paiutes were attacking a wagon train at Mountain Meadows.[110] He sent two different directives to Isaac C. Haight to not interfere with the Baker-Fancher Company and to let them pass in peace.[111]

But when Brigham Young learned of the attack, did he approve of it?

Probably not. While there are hearsay reports from newspapers that say Brigham condoned the attacks,[112] there is evidence that Brigham did not condone the attack when he learned of it.[113] For example, during his deposition in July 1875, Brigham testified that, upon learning of the massacre from John D. Lee, he told him to stop his report as he was "feeling harrowed up with a recital of details."[114] Wilford Woodruff's journal backs up this claim.[115]

Is it possible that Brigham Young actually ordered the massacre or at least knew about the plan and didn't prevent it?

No, probably not. His letter to Isaac C. Haight commanded him to let the emigrants pass through the territory in peace,[116] and his letter to William H. Dame showed he was not aware of the massacre after it happened.[117]

So why do people associate the Mountain Meadows Massacre with Brigham Young?

The massacre took place while he was both the president of the Church and the governor of Utah territory.[118] William Bishop,[BIO] the attorney for John D. Lee, wrote an introduction to Lee's 1877 Mormonism Unveiled, where he blamed Brigham Young for what unfolded.[119]

Were there any attempts to arrest Brigham Young?

Yes. Judge Elias Smith[BIO] issued a warrant for the arrest of Brigham Young on May 12, 1859, to Robert T. Burton,[BIO] Sheriff of Salt Lake County.[120]

Later, in July 1875, Brigham Young was called to Beaver to attend proceedings and give evidence.[121] That same month he was deposed, and Brigham answered questions related to the massacre and denied any role in planning it.[122]

Who are the "Missouri Wildcats" and how were they involved with the massacre?

The "Missouri Wildcats" (sometimes spelled "Americats"; "Mericats"; "Merry Cats" in various reports) were a group that reportedly joined the Baker-Fancher wagon train at some point and harassed both Native Americans and Mormon settlers.[123][124]

Did the Church try to blame the massacre on the Native Americans?

Most early reports of the massacre from Latter-day Saints (including the perpetrators) blamed Native Americans.[125] For example, George A. Smith[BIO] and James McKnight[BIO] wrote a report on August 6, 1858, which primarily blamed Native Americans.[126]

Brigham Young would also accept rumors blaming the Native Americans for the massacre as true.[127] According to the December 1857 report to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, the Native Americans admitted to participation in the massacre but said that the "Mormons persuaded them into it."[128]

Was anyone actually tried in court and convicted?

Yes. John D. Lee was tried, convicted, and executed for his participation in the massacre.[129] Lee was the only person brought to justice for participating in the massacre.[130]

It took twenty years from the time of the massacre to John D. Lee being convicted. Why did it take so long?

There were multiple reasons for the delay. Local and Federal inquiries into the massacre were being made as early as 1859.[131] At the same time, federal Indian agent Jacob Forney[BIO] was also making inquiries into the massacre.[132] In 1858, James Buchanan offered amnesty to the participants in the Utah War, which may have caused confusion on whether this covered the perpetrators of the massacre.[133] The American Civil War also delayed efforts to investigate the massacre fully.[134]

Brigham Young blamed the federal government for delaying the judicial process to "inflame public opinion against our community."[135] Others blamed the Latter-day Saints for delaying the process by being uncooperative with investigators to protect their own.[136]

Did the Church leadership use violent rhetoric against non-Mormons?

Yes. Around the time of the massacre, Latter-day Saint leaders used inflammatory language against the U.S. Government and the enemies of the Saints in the territory.[137]

Did the "Oath of Vengeance" that Latter-day Saints made for the murder of Joseph Smith factor into the massacre?

Possibly.[138] An oath or covenant for Latter-day Saints to "avenge the blood of the prophets" was a feature of the Nauvoo-era endowment ceremony.[139][140] However, sources differ on whether participants understood that they were to pray to God to avenge the martyrs or perform the vengeance themselves.[141]

Was the doctrine of "blood atonement" somehow related to the massacre?

No, however this type of rhetoric used by some Church leaders at the time contributed to the polarization of Latter-day Saints and non-Latter-day Saints in the territory.[142]

Related Question

What is blood atonement?

Read more in Blood Atonement and Capital Punishment

Did Brigham Young order the destruction of the monument at the site of the Massacre?

Possibly. The only sources for this claim come from secondhand reports that say Brigham ordered a monument at the site to be removed.[143][144]

Did the Church posthumously restore John D. Lee's temple blessings?

Yes. At the request of some of his descendants, Lee's temple blessings were restored on May 8–9, 1961, by authorization of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve.[145]

Did the Church ever make an official statement or apology for the massacre?

Yes. The Church has made many statements about the massacre condemning it,[146][147] including an official apology at a memorial service held on the 150th anniversary of the massacre.[148]

- Jace

“I have heard so many conflicting stories about this event that it was nice to read the details on Mormonr that cleared up much of my confusion as to what happened, why, and who was responsible. Thank you.” - Craig M. M.

“Suspicion, prejudice, rumors, and false accusations all contributed to the massacre. Adding to the mix was the believed imminent attack by the U S Army against the Mormons which increased both the fears, anger and hatred by the LDS against all “gentiles.”” - Ron

“This is a great, succinct version of the facts as best as can be reconstructed. Some things are still murky about the event - the only survivors from the wagon train were children and the perpetrators rarely discussed it (and generally deflected blame at others when they did.)” - Emerson

“Great article. I hadn't realized until reading this that the John Lee who wrote Mormonism Unveiled and who was executed for the MMM were one and the same. Why on earth would anyone want his ordinances restored? Was it basically trying to do work for the dead?” - K.

“Great article. Most people frame Brigham for the massacre but knowing all the factors of the time and facts helps to know the truth. Very sad and definitely not justified. But not the church’s fault as a whole as how it is usually portrayed.”